- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

Characodon sp. 1

English Name:

Rainbow Characodon

Mexican Name:

Mexclapique arcoiris

Original Description:

undescribed species

Holotype:

undescribed species

Terra typica:

undescribed species

Etymology:

undescribed species

The genus was erected by Günther in 1866. He didn't explain why he had chosen this name, but it is obvioulsy refering to the typical dentition. The name of the genus can be derived from the ancient Greek with Χάραξ (chárax), meaning "a pointed stake" and ὀδόντος (ódóntos), the genitive of ὁδούς (ódoús), the tooth. So the name of the genus can be translated with "a tooth like a pointed stake".

Synonyms:

Characodon garmani Meek, 1904

Characodon lateralis Günther, 1866

Distribution and ESU's:

The Rainbow Goodeid is endemic to the federal state of Durango. It is historically known from an area directly north of the town of Nombre de Díos encompassing the Río La Villa and the Arroyo Las Compuertas including some large springs like the Ojo de Agua Los Berros and the Ojo de Agua de San Juán. It disappeared from several historically known places like the Ojo de Agua de San Juán, probably due to exotic fish species. It is actually known from the springs in Los Berros and a tiny spring on a private property in La Constancia. One subpopulation, the Los Berros subpopulation, is accepted. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

Within Characodon sp. 1 we are able to distinguish one ESU. We use the ESU abbrevaitions given by John Lyons, who groups all Characodon for now as Characodon sp. Chrsp8 is in use for the fish of springs in San Juan, Los Berros, La Constancia and Nombre de Díos. Some of these populations are extinct, but at least the ones in Los Berros and La Constancia remained.

The left map shows the Río San Pedro basin from the Hydrographic Region Presidio-San Pedro on a Mexico map. The Rainbow Goodeid is known from the Río Durango (DUR) subbasin, shown on the right map:

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Critically Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Critically Endangered/declining: „The taxonomy and relationships of the Characodon populations occupying the upper Tunal and Durango river drainages in the upper Mezquital River basin in the state of Durango are currently unresolved. Originally, a single species, C. lateralis, was recognized, which occupied a series of semi-isolated spring systems near the city of Durango. However, the locality given for the original collection of the species, “Central America”, was clearly erroneous and the type material could not be attributed to a specific spring system (Miller et al., 2005). In the 1980’s, the population in the springs near the town of El Toboso was described as a separate species, C. audax, based on morphology, with the remaining populations considered C. lateralis (Smith and Miller, 1986). However, more recent genetic analyses revealed little difference between the El Toboso population and other nearby Characodon populations (Doadrio and Domínguez-Domínguez, 2004; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2006). Instead, these analyses indicated that populations from spring systems located above the El Salto Waterfall on the Tunal River differed from those located below the falls, suggesting that perhaps all populations above the falls could be called C. audax and those below the falls C. lateralis. However, Artigas-Azas (2014) provided strong circumstantial evidence that the type of C. lateralis probably came from somewhere near the city of Durango above the falls, making it an inappropriate name for populations below the falls. Recent morphological analyses have indicated significant differences among ten populations, nine from above the falls and one from below, with the El Toboso population the most distinctive (Tobler and Bertrand, 2014). Given uncertainly about which populations the name C. lateralis actually refers to and the discordance between the morphological and the genetic distinctiveness of the nominal C. audax from the El Toboso Springs, we have chosen to refer to all populations from the Tunal and Durango River drainages as “Characodon species”, pending a comprehensive revision of the genus. We have also identified nine ESUs, seven from above the falls and two from below, based on a combination of genetic, morphological, and zoogeographic information. Regardless of what their taxonomic affinities are, all of the Characodon species ESUs are in serious trouble. Three ESUs have gone extinct in the last 20 years and the remaining six have all suffered steep drops in abundance (Artigas-Azas 2002, 2014). Declines have been caused by the drying of springs and streams owing to groundwater pumping and water diversions and by the introductions of non-native fish species. Chrsp1, the nominal C. audax from the El Toboso Springs, is critically endangered. Chrsp2, from the Cerro Gordo and El Carmen Springs and from the San Rafael and Las Moras streams, is also critically endangered and persists in small numbers only in the El Carmen Springs and in the Las Moras Stream in the town of San Rafael. Chrsp3, from the Los Pinos Springs and outlet, is extinct in the wild, with the last specimens collected in the late 1990’s. There are a few captive populations in Mexico, the United States, and Europe. Chrsp4, from the Guadalupe Aguilera, Laguna Seca, and Aguada de las Mujeres Springs and the Peñon del Aquila Reservoir, is critically endangered and current exists only in the Guadalupe Aguilera Springs. Chrsp5, from the San Vicente de los Chupaderos Springs and the Sauceda River, is extinct with no captive populations. The last collections date from the early 1990’s. Chrsp6, from the Abraham Gonzáles, Ojo Garabato, and 27 de Noviembre springs, is critically endangered but is still found in small numbers in all three springs. Chrsp7, from the Puente Pino Suárez Stream, is also critically endangered. Chrsp8, known from the Ojo de Aqua de San Juan, Los Berros, Ojo Nombre de Dios, and La Constancia springs, all located below the El Salto waterfall, is critically endangered and has disappeared from the Ojo Nombre de Dios Springs. Chrsp9, from the Amado Nervo Stream, also located below the El Salto Waterfall is probably extinct in the wild, with the last specimens observed in 2005. A small number of captive populations exists in Mexico, the United States, and Europe.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

The habitats are similar to the ones that Characodon lateralis inhabits: Marshy pools, spring-fed ponds, springs and their outflows with abundant submergent vegetation (Myriophyllum, Ceratophyllum, Potamogeton and Scirpus). Concerning the substrates predominate silt, clay, mud, sand, soft marl, gravel and rocks. The currents are usually slight to none, occassionally moderate, the water is clear to turbid. The Rainbow Characodon prefers depths of less than 0.5m (Miller, 2005).

On a survey of the GWG in 2015, the group went to several places, where the Rainbow Goodeid occured within the past 25 years. The Ojo de Agua de San Juán looked like a wonderful spring for Characodon, but didn't reveal a single specimen. The spring fed pond was populated with different Poecilids (Xiphophorus hellerii, Poecilia mexicana, Gambusia sp.), Tilapia and Tetras (Astyanax mexicanus). Even the outflow, which was known to reveal good stocks of this Goodeid species only a couple of years ago, showed up exclusively exotics. The group was able to survey just one spring within the close by spring area in Los Berros with few fish in the main spring (probably due to predatorious crayfish), but a nice stock in a neighbouring spring with only one metre in diameter. Here Characodon sp. 1 occured together with Xiphophorus hellerii. Another habitat surveyed was a tiny spring-pool on a private property in La Constancia, where the species occured in low numbers together with Green Swordtails.

Biology:

Young were captured from 0.8 to 11mm standard length between March 13th and September 2nd. This indicates a protracted reproductive season extending from at least early March through August. Fitzsimons (1972) saw in shallow water of the Ojo de Agua de San Juan fish moving around in large aggregations, retreating to deeper places when disturbed.

On a survey of the GWG to the La Constancia spring in January 2015, the group was able to find small fry.

Diet:

Characodon sp. 1 has got bicuspid teeth in the outer series (a few smaller ones are conical) of adult fish, and small conical in the inner series. This dentition suggests an omnivorous feeding habit, but young fish have only conical teeth, so they are definitely carnivorous. The gut of this species is short, so it seems to feed mainly carnivorous with some plasticity concerning nutriment, which would explain observations of people seeing this fish feeding from aufwuchs and filamentous algae in the habitat.

Size:

The maximum known standard length is about 63mm (Miller et al., 2005).

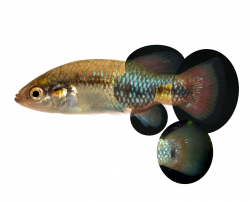

Colouration:

Characodon sp. 1 can be a very colourful species. It is olive-brown in both sexes. Females show two to seven prominent dark blotches in the midline, mostly not reaching the caudal peduncle. The lower part of the head until the origin of the anal fin is coloured creme or yellowish, the opercle has got a green glimmer, the belly is bluish. The fins are yellowish or clear in adult females. The males show red unpaired fins, changing the colour before the black terminal band into yellow. The body sides are coloured reddish, becoming deep red in older males. The scales are bluish-green. Older males appear more red than younger ones. The midline shows very few dusky and diffuse blotches and a broad and dusky lateral band. The area behind the opercle is more prominent dark. The belly from the snout to the origin of the anal fin is coloured mainly creme or yellowish, the opercle with a greenish glimmer.

Sexual Dimorphism:

Males and females of the Rainbow Characodon are not always easy to distinguish. An always safe characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Characodon sp. 1 have a slightly bigger Dorsal fin than females. The difference in colouration is sometimes clear and very distinct, but sometimes males display a female colour pattern. When there is a clear colour difference, then males have its unpaired fins coloured reddish or red, sometimes in combination with yellow, with the colour extending onto the (at least) lower posterior part of the body. The back can be overlaid by blue or turquise scales. The unpaired fins display a more or less broad black terminal band and numerous black lateral blotches coalesce to a lateral band. Females are tonelessly brown coloured with clear to whitish unpaired fins. They display a regular or irregular serious of more or less numerous black lateral blotches.

Remarks:

In all Characodon species we find different varieties of colouration of males in one population. Usually red finned males are most frequent, but (maybe even changing by year) other varieties might take over this role. While a German surveyor found in Los Berros (Characodon sp. 1) red bellied males dominating in 2005, the GWG group surveying the same habitat ten years later didn't find any male with red. All males had a typical female colour pattern. It is known from Characodon sp. 2 from Amado Nervo, that usually males with clear unpaired fins occured in the wild, but few males displayed a reddish or yellowish colour. Different populations from Characodon lateralis showed up male fins from clear to reddish, crimson red, dark red and sometimes even totally red body, and even the black of fish from El Toboso varies, so males can appear with red unpaired fins and less broad black terminal band. In aquariums, usually red finned males (or totally black finned from El Toboso) dominate and this colour gets more intense, so less coloured male types slowly disappear.

All Characodon (except most of the time the one known female of C. garmani) were called Characodon lateralis until the middle of the 1980's, suggesting that the unknown type locality was eventually close to Los Berros. In 1986 then, Smith & Miller described Characodon audax from the vicinity of El Toboso. The specimens from this location display black coloured unpaired fins, and this together with its isoltaed occurence was seen as the main character to distinguish this species from the red finned Characodon lateralis. In the early years of this Millenium, phylogenetic studies of Domínguez-Domínguez however revealed, that all red finned populations north of the waterfalls of El Saltito were closer related with the black audax from El Toboso than with the red finned populations south of the El Saltito fall. This resulted in calling the populations above the fall Characodon audax and the ones below the fall Characodon lateralis. The last study by Sherman et al. suggested to accept that the type locality of Characodon lateralis is somewhere close to Durango and to call therefore all specimens above the Saltito fall Characodon lateralis, which resulted in synonymizing Characodon audax with Characodon lateralis, but made it necessary to describe the species below the waterfalls, now two and called Characodon sp. 1 from Los Berros and Characodon sp. 2 from Amado Nervo.

Husbandry:

Looking on the biotopes of Characodon sp. 1, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, rocks, roots, branches, fallen leaves and river bank vegetation. Fry is eaten in some cases, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 1.5 or 2cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 150 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With rocks and vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate or swift, especially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. Additionally, aufwuchs and green algae may be taken in the natural habitat, so providing some kind of vegetables like boiled peas is a good food supplement. The species is not shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Chrsp8-DUR-LBer

Population: Los Berros (aka Ojo de Agua Los Berros, Ojo de Agua de San Juán)

Hydrographic region: Presidio-San Pedro

Basin: Río San Pedro

Subbasin: Río Durango

Localities: two separate spring areas, the Ojo de Agua Los Berros spring area and the Ojo de Agua de San Juán spring about 1.5km N of Los Berros

2. Chrsp8-DUR-LCon

Population: La Constancia

Hydrographic region: Presidio-San Pedro

Basin: Río San Pedro

Subbasin: Río Durango

Locality: spring on a private property S of La Constancia about 4km S of Los Berros