Ilyodon furcidens (incl. parts of xantusi)

JORDAN, D. S. & C. H. GILBERT (1882): Catalogue of fishes collected by Mr. John Xantus at Cape San Lucas, which are now in the U. S. National Museum, with descriptions of eight new species. Proceedings of the United States National Museum. No 5 (1882): pp 353-371

Collection-number: United States National Museum, Cat. No. USNM-9571 and USNM-30971.

Many specimens in fair condition, the largest one of a total length of about 83mm (3.25 inches), originally described as Characodon furcidens. In 1907, Carl H. Eigenmann described from Paraguay after two specimens (Cat. No. USNM-55642) mixed in with some Characiformes and "flattened out of shape as though they had been in a press" with Ilyodon paraguayense a new genus and species, correctly synonymized with the previous species by Hubbs & Turner in 1939, but taken the generic name proposed by Eigenmann as the next available after it was clear that this species was not a Characodon. In the same paper in 1939 they described Balsadichthys xantusi after the Hungarian exile and zoologist János Xántús (John Xantus), who eventually had collected the material where Hubbs & Turner found the new species. The Holotype (Cat. No. UMMZ-105997) is an adult male of 78mm standard length, collected with 26 Paratypes, all from quiet pools in a small tributary of the Río Colima at (Hacienda) Los Limones, about 2km SW of Villa de Álvarez, Colima. Concening the validity of this species, go to the chapter Remarks.

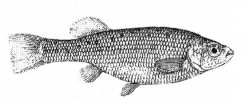

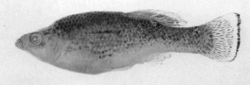

The left picture shows a drawing of one of the types of Ilyodon furcidens, the right one a photo of the Holotype of Balsadichthys xantusi:

Following the original description, the type locality should be the Cape San Lucas in Lower California (Baja California), which is definitely incorrect. Most probably there had been done mistakes when the types had been recorded: The item under "Locality " is blank for the cotype series (No. 30971) reported as from Cape San Lucas, and someone assumed without warrant that this and nearby blanks signified dittos from an entry above of Cape San Lucas. Two series in the National Museum, all collected by Xantus, are cotype lots (No. 5093 and 35338), entered as from Colima, Mexico, so it seems very likely, the types came at least from the same federal state.

The species epithet is derived from the Latin with the noun "furca" meaning fork, while the translation of "dens" is tooth. The Goldbreast Splitfin is named for its forked (bifid) teeth with the translation of its species name with "forked tooth".

The genus Ilyodon was erected by Eigenmann in 1907 without giving an explicite explanation for the reason. He indeed mentioned that the teeth were close set, but the etymology of the generic name means something slightly different. It can be derived from the ancient Greek with λύω (lýō) in the translation of "to loosen" and ὀδόντον (ódónton) the akkusative of ὁδούς (ódoús), the tooth. The prefix "in" in Latin (or asimilated il in this case) means not, without or opposite, therefore the translation could be "not to loosen a tooth" or figurative "firmly attached tooth".

Characodon furcidens Jordan & Gilbert, 1883

Ilyodon paraguayense Eigenmann, 1907

Balsadichthys xantusi Hubbs & Turner, 1939

Ilyodon xantusi Miller & Fitzsimons, 1971

Ilyodon furcidens amecae Kingston, 1979 (nomen nudum)

Ilyodon furcidens furcidens Kingston, 1979, partially (nomen nudum)

Ilyodon furcidens variabilis Kingston, 1979 (nomen nudum)

Ilyodon xantusi xantusi Kingston, 1979, partially (nomen nudum)

Ilyodon amecae Radda, 1989 (nomen nudum)

The Goldbreast Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal states of Jalisco and Colima. It occurs in the Río Salado, Lower Río Coahuayana basin, furthermore in the ríos Marabasco and Armería, the last one with its main sources, the ríos Ayuquila and Tuxcacuesco. It inhabits additionally the Río Ameca basin including its big southern affluents, the ríos Mascota and Atenquillo and the Arroyo Jolapa. Affiliated to several separate river basins, four subpopulations can be inferred: The Río Armería subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Río Ameca subpopulation, the Río Marabasco subpopulation and the Río Salado subpopulation. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Ilyodon furcidens, no ESU's are distinguished, so all populations belong to Ilyfu1. However, phylogenetic studies from Beltrán-Lopez et al. (2017) had to admit some uncertainties in the taxonomy of the genus Ilyodon, so changes may follow in the future. Actually to keep it simple and following a two species theory, we accept only furcidens and whitei. In her classification, the Goldbreast Splitfin is summarized in Clade A.

The left map shows the ríos Coahuayana (CO) and Armería (AR) basins from the Hydrographic Region Armería-Coahuayana, the Río Ameca-Atenguillo (AA) and the Río Ameca-Ixtapa (AI) basins from the Hydrographic Region Ameca, and the Río Chacala-Purificación (CP) basin from the Hydrographic Region Costa de Jalisco on a Mexico map. In the Río Ameca basin, the species occurs in the ríos Ameca-Pijinto (PIJ), Atenguillo (ATE), Mascota (MAS) and Talpa (TAL) subbasins. It is also distributed in the ríos Armería (ARM), Ayuquila (AYU) and Tuxcacuesco (TXC) subbasins from the Río Armería basin, and even reaches the Río Chacala (CHC) subbasin from the Río Chacala-Purificación basin and the Lagunas Alcuzahue y Ámela (LAA) subbasin from the Río Coahuayana basin. The specimens from other subbasins of the Río Coahuayana seem to be closer to Ilyodon whitei than to Ilyodon furcidens, nevertheless it is not fully resolved, if they really belong to this species or are even hybrids. Until we have more accurate information, we treat them as members of Ilyodon whitei here:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Least Concern

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Least Concern/declining: „As we define it, this species is widely distributed and common in the Armería basin and uncommon in the Marabasco and upper Ameca River basins. Historically, populations in the Coahuayana River basin were also assigned to this species (Miller et al., 2005), but recent genetic analyses indicate that those populations are distinct from Ameca, Marabasco, and Armería basin I. furcidens and better assigned to I. whitei (Beltrán-López et al., 2017). Populations in the upper Coahuayana basin have I. whitei morphology and appearance, whereas populations in the lower Coahuayana basin are more similar to I. furcidens in appearance and morphology, but both sets of populations are clearly distinct from I. furcidens (as we define it) genetically. Two morphotypes of I. furcidens are present in many areas of the Armería and Marabasco river basins (Lyons and Navarro-Pérez, 1990), and these were long thought to be two different species, the narrowmouthed form, I. furcidens and the wide-mouthed form, I. xantusi. However, work by Turner et al., (1983, 1985) and Grudzien and Turner (1984) demonstrated that narrow-mouthed females could produce both narrow-mouthed and wide-mouthed offspring, as could wide-mouthed females, proving that the two morphotypes were part of the same species. Ilyodon furcidens was the older of the two names and thus had priority, so the name I. xantusi is no longer considered valid. Some ichthyologists and aquarists consider populations from the upper Ameca River basin to be a separate species, I. “amecae” (Doadrio and Domínguez-Domínguez, 2004). However, genetic and morphological differences between Ameca and Armería populations are small and more recent analyses do not consider the Ameca populations worthy of even separate ESU status (Beltrán-López et al., 2017). An introduced population of what appears to be I. furcidens was discovered in 2019 in the Citala Reservoir in the Lake Sayula basin (Köck, unpublished data). Ilyodon furcidens is often the most common species at the localities where it occurs. It can reach a relatively large size (150 mm) and is sometimes consumed as food. However, numbers appear to be decreasing since 2000. Populations have declined or disappeared from several streams in the Ameca River basin because of shrinking water levels and invasions of non-native species. Within the Armería River basin, the expansion of the non-native M. salmoides, a top predator, and Poeciliopsis gracilis (Poeciliidae), a likely competitor and fry predator, has apparently resulted in the near elimination of I. furcidens from long stretches of the Ayuquila River, Jalisco (Lyons, unpublished data).“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: categoría de riesgo (category of risk): amenazada (threatened)

The habitats are pools and riffles of streams and rivers over substrates of sand, gilt, gravel, rocks, bedrocks and boulders in depths to 1.5m. The water is usually clear to murky with no vegetation or with green algae, Potamogeton and Nasturtium. The currents are not homogeneous, going from none to slow to fairly swift.

On several surveys of the GWG to habitats of Ilyodon furcidens in the ríos Ameca, Armería and Salado drainages in the years 2016-2019, the groups found this species most of the times in quite big schools of different sizes, sometimes up to hundreds of individuals. The species seemed to be anything but rare in many habitats.

Following Miller, young are born from February to July (possibly through autumn) as indicated by captures. The adult fish prefer swimming in a strong current, the young fish can be found in pools near the shore.

Teeth, gut and dentition is similar to its congener, so the feeding habits are most probably identical, means mainly herbivorous, grazing from aufwuchs and algae and collecting insects from the surface. The gut is long and suggests herbivorous feeding habits. Two trophic types can be distinguished (by their mouth) in this species: one with a narrow mouth (being suggested to be insectivore or planktivore), and one with a broad mouth (being suggested to feed from aufwuchs and algae). Both types have been seen feeding in the habitat from aufwuchs, the narrow-mouthed form additionally from the surface (Kingston, 1979).

The series of pictures below are presenting fish, we actually call Ilyodon whitei, but the same types of trophic adaptations can be found in specimens from the Armería and Salado river systems regarded as Ilyodon furcidens. The left picture shows males (fish one and three from the top) and females (two and four respectively) of a narrow-mouthed form (upper two fish) and a broad-mouthed form (lower two fish), all from the Río Tuxpan drainage, in comparison from a lateral view. The middle picture shows a drawing by D. Kingston of a broad- and a narrow-mouthed form from a top view, and the right picture several mouth forms of fish collected at the Río Tuxpan near Atenquique, all from top views:

Hubbs & Turner pointed 1939 at the variation in the colouration of this species, with age, sex and individuals. Typical for young fish is a lateral row of irregular blackish spots and bars crossing an inconspicuous axial streak as well as an irregular dorsolateral row of smaller spots and traces of other dark markings. These bars are occasionally lacking in larger young, rarely fused into a lateral band, faint to intense, small and roundish to high and narrow, often restricted to the anterior, posterior or median section. As these several variations are independent, many types of pattern are developed. In the males the bars fade out more or less completely at a length of about 35mm and are then replaced by rather dense speckling, which is strongest forward. In the females, the bars show the same variations but can be seen faintly in even the largest specimens. The dorsolateral spots usually become obsolete in the smaller females, but occasionally persist rather strongly to a length of at least 56mm. The speckling is usually little developed in smaller females, but gradually increases in intensity. Nevertheless, females are more faintly and in a finer pattern speckled than males. The ground colouration of both sexes is mainly greenish or grayish-brown on the back, becoming darker with age, and yellow to orange on the belly. This can be overwhelmed with grayish-green or brown in old individuals. The fins are normally coloured yellow to orange, the males show a dark submarginal band in the dorsal and a (most times broad) submarginal or marginal band in the caudal fin with 1 to 3 additional vertical rows of spots. Females show a narrow to wide submarginal band on the anal fin as well as in the caudal fin, where is becomes disrupted with age and fades in older females. Pelvic and Pectoral fins are usually yellow. All in all, both sexes display a very striking colouration.

At first appearance, males and females of the Goldbreast Splitfin might not be very easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Ilyodon furcidens have a much bigger Dorsal fin than females, and they are usually more intensively coloured. Many males have the caudal fin coloured partly yellow to deep orange with black rims and/or dots and blotches, sometimes even the body displays many black dots and blotches, centered in a lateral line, while adult females mostly display a lateral row of bigger dark markings with clear unpaired fins. However, there are also males without any colour markings at all and females displaying a lot of yellow, even in the caudal fin, and sometimes showing also plenty of black dots, spots and markings, so the colour is not such a clear character to distinguish sexes though it might give a good hint.

The confusion about the origin of this species is not alone shown in the original description and the wrongly assigned type locality (see above in Terra typica), but also in the description of Ilyodon paraguayense by Eigenmann in 1907: The two (crushed) types of Ilyodon paraguayense were assigned to Paraguay because they were mixed in with some Characins, collected by E. Palmer in this country. Hubbs & Turner examined in 1939 these types, and stated, that they "agree very closely not only in characters but also in superficial appearance with the types of Characodon furcidens, and it is probable that they were part of the same material, collected by Xantus in Colima."

In 1939, Hubbs & Turner described Balsadichthys xantusi in honour of John Xantus, who collected the first specimens. Even in the original description - though they pointed at the narrow relationship with Balsadichthys whitei - they discussed hybrids between Ilyodon furcidens and the new described species. They mentioned an intimate relationship of the both genera, "as indicated by their common ovarian and trophotaenial characters and evidenced by the discovery that these genera commonly hybridize in nature." They wrote furthermore: "This circumstance might even be considered a reason for synonymizing Balsadichthys and Ilyodon, but to do so would violent the consistent judgement of authors that the species with weak teeth movably set in loosely conjoined jaws of a wide, transverse mouth, should be separated generically from those with stronger teeth, tightly set in the firmly joined jaws of narrower mouths with better-developed lateral gape." and "It is not all improbable that it will be found expedient to synonymize Balsadichthys and Ilyodon...". So Hubbs & Turner recognized instinctively the narrow relationship of all these forms, they decided to let the consistent system of judging the fish after their teeth-structure persist, maybe because they saw no other, or better way to judge the fish. However, they saw this judgement not very pleasable. Nevertheless, it took another 30 years till this synonymizing had been done finally (Miller & Fitzsimons, 1971), mainly because both trophic forms can be found at the same locations, but not always. Sometimes there is only the furcidens-type represented, sometimes the xantusi-type, and sometimes both with many intermediates, so hybridisation seemed to be very likely.

In her doctor thesis in 1979, Dolores Kingston split the species Ilyodon furcidens and xantusi in several subspecies, based on morphological differences. Following her, the nominotypical subspecies Ilyodon furcidens furcidens became restricted to the ríos Armería, Salado and El Tule drainages, Ilyodon furcidens amecae to the Río Ameca system, Ilyodon furcidens tuxpan to the upper Río Coahuayana, the Río Tuxpan, and Ilyodon furcidens variabilis to the Río Jiquilpan (Río La Labora in her thesis). Ilyodon xantusi again, she split into Ilyodon xantusi xantusi from the ríos Chalaca, Armería, Salado, El Tule and Coelcomán drainages, while Ilyodon xantusi latos became a distinct form from the Río El Tule drainage, living sympatric with the other subspecies. However, the results have never been published validly. The reason therefore is the US-American jurisdiction, that a thesis doesn't count as an official publication. Nevertheless, Alfred Radda took over one of these name and gave it as Ilyodon amecae species rank in 1989. Today, all of these species and subspecies descriptions count es Nomina nuda (names without value), and some of them would be either fully or partially regarded as members of Ilyodon whitei.

The upper row shows pictures of the Kingstons types of Ilyodon furcidens furcidens, furcidens amecae and furcidens tuxpan, from left to right, the lower row those of Ilyodon furcidens variabilis, xantusi xantusi and xantusi latos, also from left to right. Ilyodon furcidens tuxpan and xantusi latos would belong completely to Ilyodon whitei following the recent classification, Ilyodon furcidens furcidens and xantusi xantusi only with populations from the Rio Coahuayana except for the Salado river. Only Ilyodon furcidens amecae and furcidens variabilis would belong completely to Ilyodon furcidens. However, all these subspecies are not validly described:

In 1980, Turner & Grosse hypothesized that Ilyodon furcidens and xantusi are conspecific, representing different trophic forms as they sampled a dichotomous population in the Río Armería and one in the Río Coahuayana and discovered little or no allozyme differentiation between the presumptive species in either location. They suggested intraspecific polymorphism. In 1984, Grudzien et al. collected Ilyodon at four locations along the Río El Terrero and one of its tributaries, the Río El Tule, and examined 36 gene loci. They detected 15 loci being polymorphic, but the detected variation has not been connected with one of the both trophic forms. In contrary: they varied independently from both forms in the same value, so there could not been detected any genetic difference between furcidens and xantusi. A similar result gave the examination of the kind of chromosomes in Ilyodon through Turner et al. in 1985: surprisingly they found a different number of metacentric chromosomes in fish of the Río Coahuayana basin, so-called cytotypes, starting with 0-2 up to 16! Such a variation is very rare among teleosteen fish at all. However, genic and chromosomal divergence are clearly uncoupled in Ilyodon and a certain number of metacentric chromosomes is not typical for one of the both trophic forms. So finally, it is neither genetically nor by the number of metacentric chromosomes possible to distinguish furcidens from xantusi. Considering that in many habitats both trophic forms can be found (even in the type material of furcidens), the final consequence would have to be to see both forms as members of one species, what Turner et al. did, but only for the Río Coahuayana populations. Ilyodon xantusi stayed valid for the Río Armería population until Lyons & Navarro-Perez (1990) synonymized both species completely. However, we point on the fact, that the taxon xantusi was in use for fish that belong nowadays to Ilyodon furcidens and whitei.

The last phylogenetic studies on Ilyodon were done by Beltrán-Lopez et al. in 2017. While the authors found evidence of accepting different clades among Ilyodon whitei, Ilyodon furcidens was treated as just one clade, including the populations from the ríos Ameca, Armería, Chalaca and Salado. The populations from the Río Coahuayana were placed closer to Ilyodon whitei in this study and were therefore treated as this species. However, the fact remains, that we find different trophic forms exclusively in the ríos Armería and Coahuayana basins which makes it an interspecific phenomenon. The Río Coahuayana populations (except for the Río Salado population) remain however difficult in denotation.

Hieronimus (1989) sampled Ilyodon furcidens in a small creek above San Antonio, finding differences mouth forms in the colour of their caudal fin (orange without markings = furcidens; yellow with black makings = xantusi). Keeping the fish in tanks, the differences disappeared and the fish looked similar to each other.

Comparing all Ilyodon-forms (including whitei and the former cortesae), there is not much difference (even phylogenetically) between them all. The genetic distances (intraspecific pairwise uncorrected "p" distances) comparing the Cytochrome b gene between Ilyodon furcidens, the former xantusi and whitei is low, only p=0.3 to 1.7% (Domínguez et al., 2004). This value is even lower than between some populations of Ilyodon whitei (1.5 to 1.7%, which is still very low)! This genus is definitely in a specification process, which makes it very difficult for scientists to classify the different forms.

The genus Balsadichthiys is one of only five that have been erected exclusively for Goodeid fish and lateron became synonyms. It goes back to C. L. Hubbs (1926), who placed Goodea whitei in it. It was seen as genus similar to Ilyodon, but with loose teeth instead of firmly attached, that's why Hubbs and Turner described in 1939 out of a sampling from Ilyodon furcidens from the Colima region the species Balsadichthys xantusi for fish from the ríos Armería and Coahuayana with loose teeth. After understanding the existance of different trophic forms of one species in even one river, the genus was withdrawn and the species Balsadichthys xantusi seen as a synonyme of Ilyodon furcidens. The etymology of the generic name goes partly back to the ancient Greek. The Río Balsas gave it the name, and combinded with ἰχθύς (íchthús, íchthýs), the Greek word for fish, the generic name can be translated with "Fish from the Balsas (river)".

Looking on the biotopes of Ilyodon furcidens, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, roots, branches, fallen leaves and vegetation in the corners of the aquarium. Fry is usually not eaten, so it is easy to get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 120 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With roots and vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks, combined with maybe some bamboo or reed stems do best with this species. The current should be moderate to swift, and due to the occurence in creeks and rivers, rich with oxygene. The species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from algae and aufwuchs, additionally small insect larvae and Crustacean, so feeding with similar food, means algae overgrown structures, vegetables, water fleas and other small food from animalistic sources will be best for this fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is not shy at all.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 26°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 22°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 23 or 24°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (28°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction might stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 22°C over the winter time to regulate reproduction.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Ilyfu1-PIJ-RAme

Population: Río Ameca

Hydrographic region: Ameca

Basin: Río Ameca-Atenguillo

Subbasin: Río Ameca-Pijinto

Locality: Río Ameca, correct location point not yet determined

2. Ilyfu1-ATE-ADav

Population: Arroyo de Ávalos (aka Arroyo Dávalos, Río Diabolos, Arroyo Diabolos)

Hydrographic region: Ameca

Basin: Río Ameca-Atenguillo

Subbasin: Río Atenguillo

Locality: Arroyo de Ávalos, at the bridge (Puente) de Ávalos

3. Ilyfu1-AYU-AMan

Population: Arroyo Manantán

Hydrographic region: Coahuayana-Armería

Basin: Río Armería

Subbasin: Río Ayuquila

Locality: Arroyo Manantlán, right before it merges into the Río Ayuquila

4. Ilyfu1-ARM-Com

Population: Comala (aka Barranca de la Tía Barragana, 1st. bridge in Comala)

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Armería

Subbasin: Río Armería

Locality: Barranca de la Tía Barragana, at Comala

5. Ilyfu1-LAA-Cuau

Population: Cuauhtemoc

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Coahuayana

Subbasin: Lagunas Alcuzahue y Ámela

Locality: Río Grande in Cuauhtemoc, at the bridge, and affluent of the Río Grande about 900m S of this point

6. Ilyfu1-TXC-Jiqui

Population: Río Jiquilpan (aka Jiquilpan)

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Armería

Subbasin: Río Tuxcacuesco

Locality: Río Jiquilpan, N of Ocampo