Alloophorus robustus

BEAN, T. H. (1892): Notes on Fishes collected in Mexico by Professor Dugès, with Description of new Species. Proceedings of the United States National Museum. No 15: pp 283-287

Collection-number: United States National Museum, Cat. No. USNM-43760.

The Holotype is an adult female of 107mm standard length, collected by A. Dugès. He sent several specimens to the Museum on August the 24th, 1891. A second fish is treated as male Allotype, cataloged under Cat. No. USNM-437662. Another specimen got Cat. No. USNM-37834, five more were summarized under Cat. No. USNM-41973. Concerning the type locality, get your information from the chapter "Terra Typica".

In 1904, Charles Tate Regan described Zoogoneticus maculatus after three individuals collected by A. C. Buller from the Río Grande de Santiago. In his opinion this species differs in head size and length of caudal peduncle from robustus. However, these differences were regarded to be not enough to separate the species and it is therefore treated as a synonym of Alloophorus robustus. Nowadays phylogenetic studies prove differences between the eastern populations ("robustus") and the western ones ("maculatus"), but it is not clear yet if they can be regarded as two separate species.

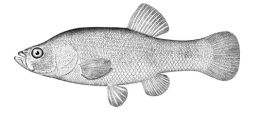

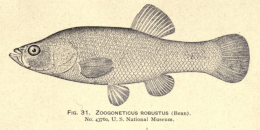

Drawings of the Holotype of Alloophorus robustus:

There is a lot of confusion concerning the origin of the Holotype. Tarleton Bean indicated the type location of the Holotype (and all other Alloophorus sampled by Dugès) being simply "Mexico", but as he described several species from a collection of Alfredo Dugès from 1891, where most of them had been collected in the state of Guanajuato, this was seen as a hint of a more detailed location information (e.g. Jordan and Evermann, 1896) for the type of Alloophorus robustus (and the male Allotype from this collector is indeed labeled with "Guanajuato"). But again, there is a sign attached on the Holotype (at least since when Hubbs and Turner studied the fish in the late 1930's) defining its origin more precisely as "Patzcuaro, Mex.", which is a different drainage. This was accepted since then as the correct type location, but has to be seen with some reluctance as Jordan and Evermann (1896) gave the origin of all Alloophorus of Dugès' collection with Guanajuato and Hubbs and Turner (1939) mentioned that all but the Holotype were labeled "Guanajuato" when they saw them. Again, the fish cataloged under Cat. No. 37834 and 41973 are still labeled "Mexico" in the Smithsonian Museum despite of what Hubbs and Turner claimed, while the Holotype is labeled "Pátzcuaro" and the Allotype "Guanajuato". However, it seems obvious that all fish go back to the collection from one single location.

The species name can be derived from the Latin and means "strong". Bean didn't explain why he had chosen this eptithet, but compared with other representatives of the genus Fundulus (wherein Bean placed this fish), this species is stronger and bigger, so maybe this was the reason. Another, also reasonable possibility would be the strong jaws of this fish that inspired Bean to this species name.

The genus Alloophorus was erected by Hubbs and Turner, published by Turner in 1937 and taken from the manuscript of the famous monography about Goodeids that Hubbs & Turner finally published together in 1939. It is "characterized chiefly by fundamental differences in the structure of the ovary and of the trophotaeniae." The generic name is derived from the ancient Greek. The word ἄλλος (állos) means different and ᾠόν (óón) is the Greek term for egg. To carry something or to bear something is φόρος (phóros) in Greek, and together with the word egg it simply means "ovary". Alloophorus can therefore be translated with "a different type of ovary".

Fundulus robustus Bean, 1892

Fundulus parvipinnis Garman, 1895

Zoogoneticus robustus Meek, 1902

Zoogoneticus maculatus Regan, 1904

The Bulldog Splitfin belongs to a few Goodeid species with a large distribution range. It is historically known from the federal states of Guanajuato, Jalisco and Michoacán and occured at the type location, the endorheic Lago de Pátzcuaro, with surrounding springs and tributaries, the adjacent endorheic Laguna de Zirahuén including the Estanque Las Condembas (Lago de Opopeo), and the likewise endorheic Río Grande de Morelia basin with the Lago Cuitzeo, several springs of the Río Grande de Morelia, the Presa Cointzio, the Laguna de Yuriría and several affluents of the Cuitzeo lake. The historical range includes furthermore the ríos San Antonio (Río Santa Bárbara) and Cupatitzio in Uruapán, Río Balsas drainage, the Río Angulo drainage with the Lago Zacapú, and several northern tributaries of the middle Río Lerma like the ríos Laja, Turbio and Guanajuato. More collection sites are known from the Río Duero drainage (a lower Río Lerma affluent) including several spring areas (Presas Orandino and Verduzco), the Lago de Chapala with the isolated Lagos Los Negritos E of the lake and subsequent sections of the Río Grande de Santiago, and finally the Presa San Juanico and other habitats in the Río Tepalcatepec headwaters in the Cotija region, Río Balsas drainage. Lyons (2011) reported that the species disappeared from the Lago de Chapala, the adjacent Río Grande de Santiago and the Río Lerma and most of its tributaries. It is no more inhabiting the Laguna de Yuriría and lost its last stronghold N of the Río Lerma in a spring in San Francisco del Rincón, so possibly no habitats in the states of Jalisco and Guanajuato (except for N shores of the Cuitzeo lake) have remained. It has become rare in many other habitats, larger stocks can be found only in some springs of the Río Duero drainage, the spring at the Molino Viejo de Chapultepec (Lago de Pátzcuaro drainage), the Lago Zacapú and the La Mintzita spring (Río Grande de Morelia drainage). Taking in consideration its affiliation to different separate river drainages respectively endorheic basins and phylogenetic results, ten subpopulations in two lineages can be inferred: The Lago de Pátzcuaro subpopulation (type subpopulation), the adjacent Río Grande de Morelia subpopulation (including the Lago Cuitzeo), the Río Angulo subpopulation (including the Lago Zacapú) and the possibly Extinct lagunas de Zirahuén and Yuriría and Middle Río Lerma subpopulations, the last one encompassing several rivers in Guanajuato like the ríos Turbío, Guanajuato and Laja. Representatives from these six drainages belong phylogenetically to one lineage (Lineage A) with respect to the following four ones, which again form a distinct lineage (Lineage B) and probably even a separate to be described species: The Río Duero subpopulation (lower Río Lerma basin), the Cotija subpopulation (upper Río Balsas drainage), the Río Cupatitzio subpopulation, also in the Río Balsas headwaters in and S of Uruapan and the Lago de Chapala-Río Grande de Santiago subpopulation, now possibly extinct except for the isolated Lagos Los Negritos about 10km E of Sahuayo. Further studies to reveal the phylogenetic relationship within this species are required. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Alloophorus robustus, actually four ESU's are distinguished. The first one (Alpro1) is in use for specimens from the Lago de Chapala and connected rivers like the lower Río Lerma, the Río Duero with the famous springs of La Luz and Orandino, the lakes of Los Negritos and watersheds southeast of Chapala like the region of Cotija, the Presa de San Juanico, the bath at Tocumbo and the spring system at Uruapán. This ESU (corresponding with Lineage B named above) comprises eventually a separate to be described species.

Alpro2 encompasses populations from the Lago de Cuitzeo and Zacapu basins, Alpro3 those from and north of the middle Río Lerma (Río Turbio, Río Guanajuato, Río Laja). The fourth and last ESU, Alpro4, is in use for fish from the type location (Lago de Pátzcuaro) and connected waterbodies and from the Lago de Zirahuén. These three ESU's form Lineage A.

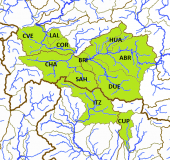

The left map shows the Río Tepalcatepec (TE) and the Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo (TI) basins of the Hydrographic Region Balsas, and the Lago de Chapala (CH), Río Santiago-Guadalajara (SG), Rio Lerma-Chapala (LC), Río Lerma-Salamanca (LS), Río Laja (LA) and the Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC) basins of the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago on a Mexico map. The middle map shows the eastern half of the distribution area of the Bulldog Splitfin, corresponding with Lineage A, the "true" Alloophorus robustus, encompassing the whole Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Laguna de Yuriria basin with its three subbasins, the lagos de Pátzcuaro (PAT) and Cuitzeo (CUI) and Laguna de Yuriria (YUR) subbasin, then the nearby Lago de Zirahuén subbasin (ZIR), Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo basin, and the Río Angulo subbasin (ANG), Río Lerma-Chapala basin. It could be found in two subbasins of the Río Laja basin, the Río Laja-Celaya (LAC) and the Presa Ignacio Allende subbasin (PIA) and in the whole Río Lerma-Salamanca basin, but became very scarce in the watersheds there. To this basin belong the Río Salamanca-Río Ángulo (SAN) and the Río Solís-Salamanca subbasins (SOS) alongside the Río Lerma, the Arroyo Temascatío (TEM) and the Río Guanajuato subbasins (GUA) and the three Río Turbio subbasins, the Río Turbio-Presa Palote (TPP), the Río Turbio-Manuel Doblado (TMD) and the Río Turbio-Corralejo subbasin (TCO). The right map shows the distribution of Alloophorus robustus in the west, corresponding with Lineage B, eventually a separate to be described species, restricted mainly to the Río Lerma-Chapala basin where it inhabits the watersheds along the Río Lerma, meaning the Río Ángulo-Río Briseñas subbasin (ABR) and the Río Briseñas-Laguna Chapala subbasin (BRI) and its affluents, the Río Duero subbasin (DUE) and the Arroyo Huascato subbasin (HUA). It occurs (partly) still in the Río Sahuayo subbasin (SAH) and the Laguna Chapala subbasin (CHA) of the Laguna Chapala basin, but probably no more in the consecutive sections of the Río Santiago-Guadalajara basin, so the Laguna Chapala-Río Corona (COR), Río Corona-Río Verde (CVE) and Río La Laja (LAL) subbasins. It also managed to reach the Hydrographic Region of the Balsas River where it still inhabits dams and lagoons in the Río Itzícuaro subbasin (ITZ), Río Tepalcatepec basin, and the Río Cupatitzio subbasin (CUP), Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo basin:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Vulnerable

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Vulnerable/declining: „Once known from more than 50 different localities, this species now persists at approximately 25 localities. Since 2000, it has disappeared from Lake Chapala and the adjacent Santiago and Lerma rivers, from the De la Laja River, a major Lerma tributary, and from Lake Yuriria. The species has become rare in the Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River, Lake Pátzcuaro and Lake Zirahuén basins, persisting mainly in heavily vegetated lake shorelines, spring areas, and small tributaries (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1998, 1999; Mercado-Silva et al., 2006; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2008). Losses have been from a combination of declines in water quality and quantity (e.g., Chapala, Cuitzeo) and predation and competition from introduced non-native species (e.g., Xiphophorus variatus (Poeciliidae) in the De la Laja River; Micropterus salmoides (Centrarchidae) in Lake Zirahuén). Remaining strongholds include the La Mintzita Springs in the Lake Cuitzeo basin near the city of Morelia, Lake Zacapu in the headwaters of the Angulo River drainage, a Lerma River tributary, and the Duero River drainage, also a Lerma River tributary, including the La Luz and Orandino spring-fed lakes. We recognize four ESUs based on genetic analyses and biogeography. Alpro1 is vulnerable and occupies much of the Lerma River basin (excluding the Turbio River drainage) and the upper Balsas River basin, Alpro2 is vulnerable and occurs in the Lake Cuitzeo/ Grande de Morelia River basin, Alpro3 is critically endangered and is found at only one or two sites in the Turbio River drainage in the Lerma River basin, and Alpro4 is critically endangered and known from the Lake Pátzcuaro and Lake Zirahuén basins. It persists at just one or two locations in small numbers in the Pátzcuaro basin.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: no categoría de riesgo (no category of risk)

Alloophorus robustus inhabits typically quiet waterbodies like lakes, ponds, reservoirs and slowly flowing rivers and streams. It lives over substrates of mud, sand, clay and rocks in depths of 1 to 2m. Different forms of vegetation can be found, including water hyacinths (Eichhornia), water lilies (Nymphaea), club-rush (Scirpus), Ceratophyllum, Potamogeton and green algae, but may be sparse. Brian Kabbes described in 1998 one habitat of this species, the Lago Orandino. He recorded a clear lake with a bit turbidity. Under overhanging plants, he saw Alloophorus waiting for prey. He predicated the species as shy, apparently preferring some current.

On a survey of the GWG to the Cuitzeo lake in November 2014, the group found a single juvenile male very close to the bank in about 30cm deep water in the middle of reed and aquatic vegetation. Two more individuals, a juvenile pair of about the same size was collected with a seine net in an effluent of the Molino Viejo de Chapultepec spring. The locality didn't show any vegetation, few rocks on the bank, water depth around 30cm again. A third individual, a male, was taken with an electrofishing device between dense submerse vegetation of the genus Egeria or Elodea three years later in April 2017. Already back to March 2016, a survey of the GWG to the La Luz spring, Río Duero drainage, got a batch of Alloophorus fry directly on the bank between a dense mesh of willow tree roots, the size of the fry was around 2cm. Another survey to the same locality in October 2018 revealed several adults and semi-adults. The fish were collected with a seine net in about 5m from the bank in 1.2m deep water in slightly murky water without any submerse vegetation.

Underwater-Videos:

In May 1904 Meek found 108-120mm long females containing 20-38 young fish, each of them 17-19mm long. Fry of 20-22mm SL in UMMZ collections appeared between 12. May and 12. June. A 19mm fish had been collected on 19. February in a warm (24.5°C) spring and another one of that length was captured on 9. March from Lago de Camécuaro near Zamora. Thus there is the potential for an extended reproductive period. Ovaries with embryos in various stages of development were noted between 5. May and 16. August from the Pátzcuaro lake, but young were born only during a two-month period (April - June, Mendoza, 1962). This suggests there is only one brood cycle. The average of brood size has been 23.7 young per ovary, including only 0.42% runts.

This species is characterised by a large mouth and strong jaws. The teeth are sharply conic and it’s got a relatively short intestine. This fish is probably the most highly developed carnivore in the family feeding mainly from other fish (in the gut of one Alloophorus was found a middle-sized Poeciliopsis infans.), big insects and worms. Alloophorus robustus is definitely a predator. Brian Kabbes described the way to hunt similar to that of a pike.

M. Köck reported the way of hunting in a friends aquarium. An adult pair was kept together with adult Ameca splendens and Red Swordtails in a 500 liter tank, partly dense submerse vegetation. During day, the Bulldog Splitfins didn't make an attempt to catch the swordtail and Ameca fry, but when the lights dimmed, the pair became active. When the hunted fry was hiding in the waterplants, one of the Alloophorus dashed into it and chased the fry out, the partner fed from one or two of the fry, then the predators switched their roles and the other one became the chasing part. The next morning, about 20 young fish of about 2cm length were gone.

This species shows many big blotches on its sides (extending onto belly in juveniles), that are fading in large fish. Breeding males show rarely a subterminal black band and a yellow terminal band in its median fins. Bean designated the colour as uniform pale brown with unspotted fins and the opercle with a golden tint. Wischnath meant, "according to the mood the body appears, besides gray brown, more or less dark, including the fins. In a few cases the body exhibits a dark, weakly marked spotting." However, young specimen remind of Chapalichthys pardalis with bigger and rounder spots, covering the sides.

At first appearance, males and females of the Bulldog Splitfin are not very easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Alloophorus robustus have a much bigger Dorsal fin than females. As a third character, the shape might mentioned: males are usually shorter and a shade higher than females, but to this character needs a bit experience. Normally, no difference in colouration between the sexes is visible.

The Bulldog Splitfin is the largest Goodeid species besides Goodea atripinnis, reaching a TL of 170mm or even more. Like many other predatory fish, live food, mainly fish, crayfish, big insects and worms, seem to be necessary for a successful breeding in captivity.

Riehl (pers. comm., Hieronimus) documented a phenotypical female of 150mm SL with testes and first beginnings of a Splitfin.

Though this species is widely distributed, it is not very common. On several surveys of the GWG, the participants were able to find only few specimens: a juvenile individual in the Cuitzeo lake, directly in dense reed (2014), three specimens in the Molino Viejo de Chapultepec spring system on two surveys (2014, 2016), one of them also out of dense vegetation, a group of fry in dense root mesh of trees in the La Luz spring (2016), and several adults and juveniles at the same locality with seine nets in 2018. More detailed information on the sightings can be read in the chapter "Habitat".

Looking on the biotopes of Alloophorus robustus, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with none to moderate current, structured with rocks, roots and areas with dense submerse vegetation. Intraspecific or against other fish of similar size, none to little aggession can be observed, nevertheless, the tank set up should feature areas where the fish can hide as this is part of the species' behaviour. Fry is eaten in almost all of the cases, and this seems to happen even when the quantity and quality of food is maximised and the number of places for the fry to hide is numerous. When separate brought up fry with a size of 4 or 5cm is added to the group, it usually works properly to bring them up with the adults. It is probably not possible to get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 250 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. A bit with roots and/or rocks structured tanks with dense submerse vegetation in the corners and bigger free areas to swim seem to do best with this species. The current should be low to moderate, neverteheless the oxygene level should be quite high (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, adults of this species feed from bigger invertebrates, shrimps, crayfish, tadpoles, worms, but mainly from small to middle sized fish, so feeding with similar food, means small fish, earthworms, Gammarids, shrimps and other middle sized food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. In aquarium, it additionally feeds well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally freeze dried food like Brine Shrimps is eaten greedy, but the species needs live or contentful frozen food to spawn and breed. According to its nature as an ambush predator hiding in vegetation, and in contrast to its size, this species is a bit shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially as a predatory species that concentrates waste materials quicker in the surrounding water than fish using other food sources. Therefore an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C). Some populations do even well with temperatures down to 10°C or lower over months, but this has to be oberserved carefully.

This species does very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Alpro1-DUE-LLuz

Population: La Luz (aka Presa de Verduzco)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Duero

Locality: Presa de Verduzco, E of Jacona de Plancarte

2. Alpro2-ANG-LZac

Population: Laguna Zacapú (aka Lago de Zacapu, Zacapu)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Angulo

Locality: Laguna Zacapú

3. Alpro2-CUI-PCoi

Population: Presa de Cointzio (aka small pond near Presa de Cointzio)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Laguna de Yuriria

Subbasin: Lago de Cuitzeo

Locality: small pond 1km N of the Cointzio dam (Presa de Cointzio)