Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis

BEAN, B. A. (1898): Notes on a collection of fishes from Mexico, with description of a new species of Platypoecilus. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 21 - Nr. 1159: pp 539-542

Collection-number: United States National Museum, Cat. No. USNM-48209.

The Holotype is a mature female of 48mm total length, collected by Edward William Nelson on August the 5th, 1892. No other specimens were taken with the Holotype.

The left picture shows a drawing of the Holotype of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis from Beans description in 1898, the right one the south shore of the Cuitzeo lake with the 19th century causeway connecting north and south shore:

The Holotype of this "interesting little fish" (B. A. Bean) was collected in the Lago de Cuitzeo.

This species is named for the type location, the Lago de Cuitzeo, which was spelled in earlier times "Quitzeo" in English. This lake is the oldest but second biggest in Mexico and is covering 300-400km², depending on year and month. It is astatic, and the volume and level of water in the lake fluctuates frequently. The lake is very shallow with an average depth of about 1.5m and a maximum of 3m.

The genus Zoogoneticus was erected by Meek in 1902 with quitzeoensis as type species with reference to the fact that this genus encompasses livebearing fish. The generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek with ζῷον (zóon) meaning animal, γόνος" (gónos) offspring and νέμω (néon) in the sense of distributing. The Latin suffix -ticus forms a noun from an adjective, so the name of the genus means something like "baby distributor".

Platypoecilus quitzeoensis Bean, 1898

Poecilia quitzeoensis Meek, 1902

The Picotee Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal states of Guanajuato and Michoacán. Its historically known distribution encompasses the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia drainage including the Lago Cuitzeo and the Presa Cointzio and several affluents of the lake and the river as well as springs (manantiales San Cristobál and La Mintzita). Furthermore it could be found in the Laguna Yuriría, the Lago Zacapú and the Río Angulo, the Middle Río Lerma and habitats along the Río Turbio, Middle Río Lerma drainage. It has been extirpated from the Río Lerma and possibly from the Río Turbio drainage as well as from the Laguna Yuriría. It still inhabits the Cuitzeo lake, the Presa Cointzio and springs along the Río Grande de Morelia and the Río Angulo drainage including the Lago Zacapú. Affiliated to four different drainages, four subpopulations can be inferred: The Río Gande de Morelia subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Río Angulo subpopulation, the Laguna Yuriría subpopulation and the Middle Río Lerma subpopulation. The last two ones are Possibly Extinct. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis, Molecular genetics give us the possibility to distinguish two ESU's (reference: Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2008). The first unit - Zooqu1 - encompasses populations north of the middle Río Lerma, including mainly the Río Turbio in the vicinity of the city of San Francisco del Rincón, a heavily polluted area. It has to be threated as critically endangered. The second unit is named Zooqu2 and encompasses populations within the lagos de Cuitzeo and Zacapu basins, including some springs like La Mintzita. The populations there get big numbers during the wet season, but are being reduced during the dry season for sure through the mass of fish eating birds, as we could recognize in January 2015, and have to be threated as endangered due to quite a few habitats.

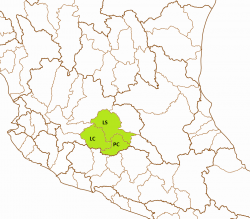

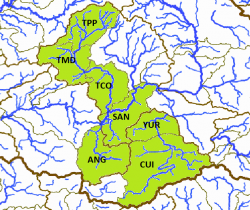

The left map shows the Lago Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC), the Río Lerma-Salamanca (LS) and the Río Lerma-Chapala (LC) basins, all from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Chapala on a Mexico map. The Picotee Splitfin is known from the Río Angulo subbasin (ANG) from the Río Lerma-Chapala basin, the lagos de Cuitzeo (CUI) and de Yuriría (YUI) subbasins from the Lago Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basin, from the Río Salamanca-Río Angulo (SAN) subbasin and the three Río Turbio subbasins, the ríos Turbio-Corralejo (TCO), Turbio-Manuel Doblado (TMD) and Trubio-Presa Palote (TPP) subbasins, all from the Río Lerma-Salamanca basin. The subbasins of the Río Lerma-Salamanca basin are or were populated (they might be extinct) with fish from the ESU Zooqu1, the three remaining subbasins are still populated with fish from the second ESU, Zooqu2. All of them are shown on the right map:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Endangered/declining: „ As currently defined, this species was known historically from the Angulo, Turbio, and Laja river drainages and Lake Yuriria in the middle Lerma River basin, and from throughout the endorheic Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia basin in central Mexico (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2007, 2008). Since 2000, Z. quitzeoensis has disappeared from many areas owing to a combination of water pollution, habitat loss from water diversions, and introduction of non-native species (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1997, 1998; De la Vega-Salazar et al., 2003, De la Vega-Salazar and Macías-Garcia, 2005; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005, 2008; Mercado-Silva et al., 2006). We recognize two ESUs based on genetic analyses (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2008). Zooqu1 is critically endangered and was known historically from the Laja and Turbio river drainages. Populations in the Laja are now gone, and nearly eliminated from the Turbio. One or two populations may still persist in springs draining to the Turbio River. Zooqu2 is endangered and known historically from Lake Yuriria, the endorheic Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia basin, and the Angulo River drainage. The populations in Lake Yuriria, Lake Cuitzeo, and the Grande de Morelia River have been eliminated, and the species persists at only a few locations. The best remaining populations are in Lake Zacapu at the headwaters of the Angulo River drainage, and La Mintzita Springs, which drains to the Grande de Morelia River near Morelia.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): A - Amenazada (threatened)

This species inhabits lakes, streams, ponds, canals and ditches over substrates of clay, silt, mud, sand, gravel, decayed organic matter and rocks. It prefers clear to muddy water with currents none to moderate and can be found in depths of less than 1m, usually less than 0.6m, pefering areas with dense vegetation including green algae, Eichhornia, Scirpus, Potamogeton, Nasturtium, Chara and Lemna.

On several surveys of the GWG to the Río Angulo drainage in 2014, 2016 and 2017, the groups found this species in dense root mesh of riparian trees in the Zacapú lake and very few near riparian grass in Tarejero. Within the Río Grande de Morelia drainage, the species was seen individual or pairwise between rocks at La Mintzita spring and was found in muddy water near the shore in the Cuitzeo lake. Two surveys to the Río Turbio drainage in 2017 were unfortunately inconclusive in finding this species.

Captures of young indicate a reproduction period from January to April. Kingston (1979) noted pregnant females and fish in all sizes of the related Zoogoneticus purhepechus in April in the Lago de Camécuaro in Jalisco. On a survey of the GWG to the Zacapú and Cuitzeo lakes in November 2014, the group was able to find many young fish with sizes about one cm or slightly larger, sugesting they were born around September, and several gravid females.

The Picotee Splitfin has got conical teeth, a short gut (a little bit longer than the total length) and a small mouth. This indicates carnivorous feeding habits, visiually locating and picking up small invertebrates like crustaceans and insect larvae.

Males are dark and mottled, with the sides, back, nape and top of the head olivaceous. Mottling in the region of the median lateral scale series may coalesce to form a lateral stripe. Antorbital pigmentation typically carries the lateral stripe onto the snout (also found in females). A series of four, typically large, posteroventral spots can be found in smaller adults. The size at which these spots fade varies. The body colour fades to pale yellow below the lateral scale series on the belly and below the eye. A pair of spots, which may coalesce, lies at the caudal fin base. The unpaired fins are dark, fading toward the margins, with the pigmentation concentrated between the rays in the dorsal and anal fins. The borders of the dorsal and anal fins each have a thin red-orange band. Melanisation is ubiquitous in the caudal fin, but typically fades somewhat terminally. The paired fins lack pigmentation. Females are olivaceous and mottled. The sides, back, nape and top of the head are dark, while the belly below the lateral series and the area below the eye are pale yellow. Two to four large spots are found on the ventral half of the posterior part of the body. These spots do not fade with age, unlike in males. A pair of basicaudal spots, which may coalesce, are visible in most specimens. The unpaired fins are lightly pigmented, giving them a dusky appearance, and these fins do not possess the red-orange margins that males display. The paired fins are clear.

Males and females of the Picotee Splitfin are easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, males typically have an orange to red terminal band on dorsal and anal fins while females display clear fins. Males are at least during courthsip more beautifully coloured while females keep their abdominal blotches, but this is not a safe character.

Originally, the Picotee Splitfin was thought to have a wide distribution, reaching even the Río Ameca basin in the west. Following studies at the beginning of this millenium, the western populations refer to a distinct species, described in 2008 (Domínguez-Domínguez et al.) as Zoogoneticus purhepechus. However, both species are hardly to distinguish and differ optically only in some minor details. Nevertheless, the situation with two distinct lines has been recognized even in earlier pylogenetic studies (Webb, 1998; pers. comm. 2010).

As mentioned above, the two species quitzeoensis and purhepechus are hardly to distinguish. The main morphological difference is the longer dorsal fin of purhepechus (13 or 14 rays to 11 till 13 in quitzeoensis), and thereof resulting divergent distances from snout to dorsal fin and dorsal fin to caudal fin. Genetically, the differences in the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene range between 3 and 3.8%, which is a higher value than it can be found between some other species (e.g. 0.6 - 1.7% between Skiffia francesae and multipunctata) - and even more than between man and chimpanzee regarding the same gene ( 3%), so both species are well defined and the results are statistically strongly supported.

The population form the middle Río Lerma basin, means from the Río Turbio in the vicinity of San Francisco del Rincón is forming a separate clade within the species. A GWG survey to the last stronghold of this species north of the Río Lerman, the Ojo de Agua de san Francisco del Rincón in March 2017 revealed no other fish in the spring except introduced Tilapia and predarorious Sunfish and Black Bass. A detailed survey of the outflow and several channel in the vicinity of the spring didnt show up any Zoogoneticus, but at least some other native fish (Goodea atripinnis, Poeciliopsis infans). However, it is quite unclear if specimens of this species still persist in the area north of the Río Lerma.

Looking on the biotopes of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis, they suggest the species may prefer dense vegetation and roots to hide. In the wild, there was little or none current to observe in the biotops of these species, so it won't be necessary in the aquarium as well. In the aquarium, the fish often hide deep in the shelter, but courting or impressing as well as fighting males can often be seen in the open water. Fry is rarely eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of space to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry is usually neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 1.5 or 2cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 80 liters, bigger ones are better for sure. Dense vegetation combined with many roots and wood and free space areas for the males to impose and fight make sense. The current should be moderate, especially as the oxygene level should be quite high (at least 8mg/l) for this spring inhabiting species.

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. The species was observed at la Mintzita spring looking for small sources of food between rocks and picking up small Copepods or organic matter. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is anything else but shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or gets too warm (25°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

This species does very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the temperature exceeds 15°C water temperature and cold periods are no longer expected. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the temperature goes below 10°C water temperature and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Zooqu2-ANG-LZac

Population: Laguna Zacapú (aka Lago de Zacapu, Zacapu)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Angulo

Locality: Laguna de Zacapú