Hubbsina turneri (including G. ireneae)

DE BUEN, F. (1941): Un nuevo Género de la Familia Goodeidae Perteneciente a la Fauna Ictiológica Mexicana. Anales de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas 2 (2-3): pp 133-141

The Holotype is a female of 65mm total length and the Allotype a male of 47mm. Both were collected on August the 19th, 1940, together with several female Paratypes of 65-73mm (the biggest one containing 71 fry of 10mm length) and male Paratypes of 40-51mm total length, and deposited without Catalogue number in the limnological station of the town of Pátzcuaro, "La Estación Limnológica de Pátzcuaro". The Holotype of Girardinichthys ireneae is a male of 22mm standard length (Cat.No. NMW-94578), collected by A. C. Radda and S. M. Calderón on February, the 15th, 2001, the Paratypes are two females of 17mm standrad length, collected the day before by Radda and M. K. Meyer. Two more Paratypes, a pair of 29.2mm (male) and 31.5mm (female) standard length, collected by Derek Lambert in July 1990, were added to the description.

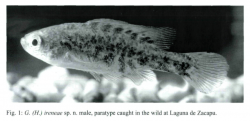

Left picture shows a drawing of the types of Hubbsina turneri, the right one a male Paratype of Girardinichthys ireneae:

The Holotype was collected in the Presa Cointzio, a dam in the course of the Río Grande de Morelia, in the federal state of Michoacán.

This species is named after the American ichthyologist Clarence Leicester Turner, probably for his important part in studying Goodeids and for publishing an important paper about this group of fish together with Carl Leavitt Hubbs, who was a dear friend of de Buen (the author named the genus after Hubbs), two years before.

The genus was erected by Fernando de Buen y Lozano in 1941 to honour Carl Leavitt Hubbs. He used the latinized female form of his surname, Hubbsina, for the generic name, meaning "Hubbs' one". Funnily enough, he managed to honour both ichthyologists who worked on the review of the Goodeidae in 1939 within one species.

Girardinichthys turneri Radda, 1984

Girardinichthys ireneae Radda, 2003

The Highland Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal state of Michoacán. It was historically reported from the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia drainage including the river itself, the Presa Cointzio (type location), the Lago Cuitzeo and some of its affluents and the Laguna Yuriría. It furthermore inhabits the flat area of the former Zacapú paleolake. Until recently known only from the Lago Zacapú, it was in 2013 additonally discovered in a tiny spring in the village of Jesús María, becoming an affluent of the Canal Patera, the main source of the Río Angulo at Villa Jiménez. This spring is about 35km ENE of Zacapú. It is probably extirpated from this spring and has not been seen in the Río Grande de Morelia basin since the late 1980's and is possibly extinct there. According to its affiliation to three drainages, three subpopulations are distinguished: The Río Grande de Morelia subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Laguna Yuriría subpopulation and the Río Angulo subpopulation. The first two subpopulations are regarded extinct. The underlined names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

Concerning Hubbsina turneri, we are able to distinguish two ESU's, corresponding with the separation into two species after Radda & Meyer in 2003. Though Lyons follows the Radda taxonomy and includes ireneae and turneri in the genus Girardinichthys, after clear phylogenetic results, the genus Hubbsina is unispecific and has to be treated as valid. Anyway, to cause no confusion, we follow the Lyons designation here with Girtu1 in use for fish from the Lago de Cuitzeo/Río Grande de Morelia basin and Girir1 for the fish from the Laguna Zacapu/Río Angulo system.

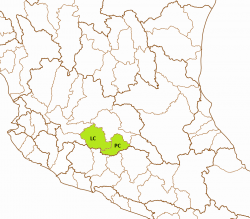

The left map shows the Río Lerma-Chapala (LC) and the Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC) basins from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago on a Mexico map. The Highland Splitfin was historically known from the endorheic Laguna Yuriría (YUR) and Río Grande de Morelia/Lago Cuitzeo (CUI) subbasins within the Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basin, and from the Río Angulo subbasin (ANG) within the Río Lerma-Chapala basin, all of them within the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago and shown on the right map. The first two basins were populated with the ESU Girtu1 sensu Lyons, which is probably extinct. Girir1 sensu Lyons was described as Girardinichthys ireneae from the Zacapú lake (Río Angulo drainage), so the third subbasin is populated with fish from this ESU:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Critically Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Girardinichthys ireneae: Critically Endangered/declining: „ Until recently, this species was considered to be part of Hubbsina turneri (DomínguezDomínguez et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2005). When Radda and Meyer (2003) subsumed Hubbsina within Girardinichthys, they split the former H. turneri into two species, G. ireneae and G. turneri. Girardinichthys ireneae, as currently defined, is known only from the upper portion of the Angulo River drainage of the Lerma River basin, primarily in Lake Zacapu and a few smaller spring-fed lakes nearby. It appears to have disappeared from the smaller lakes since 2000 and persists only in spring-fed areas of Lake Zacapu.“

Girardinichthys (Hubbsina) turneri: Extinct/no records since 1980s: „ As defined by Radda and Meyer (2003), this species was limited to Yuriria Lake in the Lerma River basin and the nearby endorheic Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basin. These two areas have been heavily polluted and modified, and no G. turneri have been observed in either area since the late 1980’s despite repeated and intensive targeted sampling (Soto-Galera et al., 1999; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005). Unfortunately, no captive populations exist, so this species appears to be extinct.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

This species lives in quiet waters with currents none to slight of lakes, ponds, canals and ditches. The substrates in the habitats are mainly mud, silt, clay, sand, rocks and decaying organic matter. It prefers depths less than 1.3m. The water is clear to usually turbid or muddy, vegetation is present and dense, mainly green algae, Potamogeton, Eichhornia, Typha and Scirpus. The Laguna de Zacapu is a spring-fed lake, drained by the Río Angulo, which divides in two streams after 20km. The habitat is 0.5 to 1m deep and the ground is predominantly of mud which leads to a translucent (greenish) to turbid water. The Highland Splitfin prefers well planted areas, where it is hiding under the aquatic vegetation, including Chara, Potamogeton, Ceratophyllum and green algae.

On several surveys of the Zacapú lake by members of the GWG (2014,2016 and 2017), the species was found to hide between roots of willow trees and fallen leaves on the ground. Kees de Jong (2013) described the habitat in Jesus María as some springs formed with concrete into rectangular basins. These basins were populated with swordtails (Xiphophorus hellerii). The water flew out in some shallow creeks trough a marshy area, more or less a densely planted swamp or flooded sodden grass. The Highland Splitfin was found together with Allotoca zacapuensis only in the creek outside of the little forest with the springs, both in small numbers.

Guillermo Mendoza took newborn fish on may the 26th, 1956, so this indicates that young are born at least from May through August. The broods are large, big females have 20 to 40 fry each. Brian Kabbes documented a territorial behaviour of this species (1999). He caught a conspicuous looking male and released it again at another place. After some time, this fish was back where it was collected before. He tried this several times with the same fish, and it came back again each time. James K. Langhammer (1991) assumes a nocturnal or crepuscular behaviour, derived from personal observations in captivity and from observations of collectors in the wild. In 2016, the survey of the GWG of the Zacapú lake extended into the dusk with the number of Hubbsina turneri found increasing conspicuously.

The teeth have not been examined in the original description, but this species feeds in captivity nearly exclusively from small Crustaceans, like Copepods and Daphnia, Nauplii of Artemia, small Bloodworms and other live or frozen food. Together with its hiding way of life and a diurnal migration of planctonic invertebrates in lakes and ponds, it seems that Hubbsina turneri is afood specialist, picking up small plantonic organisms in twlight over the ground.

Fernando de Buen described the colour of the preserved Holotype, a female, as "dark on the back and yellowish-white on the venter. On the sides it has got several dark blotches, mainly extending vertically. They appear on the venter and the lower part of the caudal peduncle. Unpaired fins are spotted, mainly the dorsal fin, the other fins are clear." He described the male Allotpye as grey on the back and the sides, yellowish on the venter. No blotches visible; only between the rays of the caudal fin there are some dark chromatophores. On the upper part of the back are some narrow longitudinal-spaces without colouration. The dorsal fin shows some dark-coloured areas between the rays, the caudal base has got some coloured blotches. The pelvic and pectoral fins are clear. The anal fin has got some blotches". Radda and Meyer wrote in their description of Girardinichthys ireneae about the colouration simply: "Males of G. ireneae sp.n. (as well as females) have numerous dark spots on body and dorsal fin."

In life, this species appears golden-brown to yellowish-brown with several irregular and different-sized blotches in both sexes. The caudal peduncle, the posterior part of the venter and the base of the dorsal fin are more prominent spotted. Some individuals show a line of blotches on the base of the dorsal fin. The lower side of the head and the anterior part of the venter are coloured golden, yellow or creme without blotches. The dorsal part appears brighter than the ventral part with smaller blotches and spots, more dusky than dark. The fins are clear with some dark speckles.

Males and females of the Highland Splitfin are not easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Hubbsina turneri have a much bigger Dorsal fin than females. A difference in colouration is usually barely visible.

Langhammer assumed already in 1999, that Hubbsina turneri differs from other Goodeids in its nocturnal behaviour: "By day it disappears into 'caves' of coconut shells and flower pots of the type used by dwarf cichlids". Possibly correlated with this behaviour is the pale back and dark venter, the reverse of colouration in other, usually diurnal, Goodeids, he stated. Langhammer also posted that "Miller collected significant numbers in deep and very turbid water, similar to Derek and Pat Lambert, who found their best collections occured after heavy rains and on overcast days." Derek Lambert said, following Langhammer again, "that the only time, he had luck on bright days was by collecting in well-shaded areas away from open water." All of these successful collections happened under conditions simulating dusk or darkness. On several trips to the Laguna de Zacapu, members of the Goodeid Working Group were looking for Hubbsina. By day it was quite hard to find them, but at dusk the appeared out of the dense roots from surrounding trees that reached into the water.

Between Hubbsina tuneri and Girardinichtys ireneae are some (but few and weak) differences. However, according to molecular and morphological studies (Moncayo-Estrada, 1993; Doadrio & Domínguez-Domínguez, 2004; Ramírez-Herrejón, 2010), turneri and ireneae are not to distinguish. Domínguez-Domínguez (pers. com., 2011) pointed at the fact, that the description of both species had been done with only very few specimens and that the differences might not be big enough to separate them from each other. At the beginning of the 1990', after the discovering of the Zacapú population and the first people talking about differences between the populations of the Zacapú and Cuitzeo lakes being significant enough to justify two species, Moncayo-Estrada in his thesis (1993) compared 30 specimens from these two lakes and the types Fernando de Buen used to describe Hubbsina turneri. Anatomically he could't find differences, morphologically he used a principal component analysis revealing no differences between both studied populations, and minor differences between the 30 specimens from the Zacapú lake and de Buens types from the Presa Cointzio (orbital length and number of caudal fin rays). A final analysis of variance brought the result, that even these differences were too small to be significant. So he observed differences between both populations, but these differences are rather caused by environmental influences than by the expression of genes: [...from which we can conclude, that it is one and the same species, and that variation is likely to be seen as an adaptation to the locality, especially if one considers the aspect of nutrition.]. Nevertheless, Radda and Meyer described ten years later Girardinichthys ireneae as a distinct species. Even the description in the genus Girardinichthys must be seen very critical as there are clear reasonable phylogenetic results and the fact, Hubbsina turneri is unique among Goodeids having the highest number of dorsal rays with the number of Anal fin rays not augmented, while both Girardinichthys species have a higher number of Dorsal and Anal fin rays. Both authors claimed an almost identical Karyotype as a sign of being members of the same genus, an opinion, that is meanwhile outdated.

Looking on the biotopes of Hubbsina turneri, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with none to moderate current, structured with gravel, rocks, roots, branches, fallen leaves and subnerse or/and river bank vegetation. Fry is usually not eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. Despite of being a delicate species, it is possible to get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 80 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With some rocks or roots and dense vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks combined with several roots and/or wood as well as dead leaves seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate, specially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small invertebrates like Copepods or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food like water fleas and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predominantly predatory fish. In aquarium, it feeds also from frozen or freeze dried food and even tablets, but rarely flake food or granulate. Additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy and might be an essential part of feeding. Due to its nocturnal respectively crepuscular behaviour, the species acts shy, usually hiding by daylight.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. This species can be kept down to temperatures of 10°C without problems for weeks. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 17 or 18°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (24°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Girir1-ANG-LZac

Population: Laguna Zacapú (aka Lago de Zacapu, Zacapu, aka Girardinichthys ireneae)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Angulo

Locality: Laguna de Zacapú