- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

Allotoca dugesii

English Name:

Bumblebee or Opal Allotoca

Mexican Name:

Thiro

Original Description:

BEAN, T. H. (1887): Descriptions of five new Species of Fishes sent by Prof. A. Dugès from the Province of Guanajuato, Mexico. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 10: pp 370-375

Holotype:

Collection-number: United States National Museum, Cat. No. USNM-37831.

The Holotype is an adult female of 60mm standard length, a second female of 64mm SL had been deposited under the same collection-number, both denoted as types by the author. They were collected and sent to Meek together with nine additional specimens by A. Dugès, collection-date unknown.

In 1940, Fernando de Buen described Allotoca vivipara from the Pátzcuaro lake, in his opinion differing in colour from Allotoca dugesii. The Holotype of 63mm, probably a female, became part of the collection of the Estación de la Limnológica de Pátzcauro. The author gave no collection number of this fish and the species is meanwhile correctly synonymized with dugesii.

Drawings of the Holotype of Allotoca dugesii (left) and of de Buens Allotoca vivipara (right):

Terra typica:

Bean suspected that the types came "probably from streams belonging to the Pacific slope of the Province Guanajuato". The exact locality is not known, as already Meek remarked, the only hint is, that they were part of a collection of Alfredo Dugès, who was active for several years in sampling fish in the federal state of Guanajuato.

Etymology:

The species is named after A. Dugès, who settled in Guanajuato, organized field trips to collect animals and sent this fish to Bean for description.

The genus Allotoca was erected by Hubbs and Turner, published by Turner in 1937 and taken from the manuscript of the famous monography about Goodeids that Hubbs & Turner finally published together in 1939. Though the authors mentioned the posterior insertion of the dorsal fin, "the more fundamental characters of Allotoca, however, are ovarian and trophotenial..." The word ἄλλος (állos) means different and τόκος (tókos) offspring, so the genus refers to the different looking trophotaenia of the fry with the generic name meaning "different offspring".

Synonyms:

Fundulus dugèsii Bean, 1887

Adinia dugesii Jordan & Evermann, 1896

Zoogoneticus dugesii Meek, 1902

Allotoca vivipara de Buen, 1940

Allotoca dugesi Smith & Miller, 1980

Distribution and ESU's:

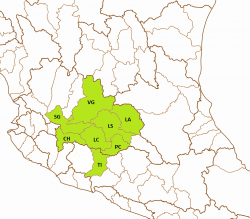

The Bumblebee Allotoca is endemic to the federal states of Michoacán, Jalisco and Guanajuato. The historical distribution encompassed the Río Lerma, the Lago de Chapala and the Río Grande de Santiago to just above Guadalajara, springs and its effluents along the Río Duero (lower Río Lerma affluent), headwaters of the Río Verde and some of its affluents like the ríos Lagos and San Pedro, northern tributaries of the Río Lerma (ríos Turbio, Guanajuato and Laja, Arroyo Grande), the endorheic Lago de Pátzcuaro basin, the lagunas de Zirahuén and Yuriría, and the endorheic Rio Grande de Morelia basin, including several springs and dams and the Lago Cuitzeo. There is one report from the E-coast of the Laguna San Marcos in Jalisco, about 12km W of the Chapala lake, and recent rumors about an Allotoca maculata respectively dugesii type fish from the Laguna de Sayula drainage near Atoyac, but these records need to be verified (likely a misidentification with "Xenotoca" cf. melanosoma). The species has been extirpated from the Río Grande de Santiago and Rio Verde drainage through water pollution. A survey of Slaboch et al. revealed in 2008 a stock N of Poncitlán, but the habitat was polluted and fishless (except for introduced Gambusia sp.) on a survey of the GWG in 2016. The last two known habitats of the species N of the Río Lerma were surveyed by the GWG in 2017. The habitat S of Irapuato (close to the Río Guanajuato) has altered into a muddy, stinky channel without any fish and the habitat E of Corralejo de Hidalgo (Río Turbio) was populated only with Guppys (Poecilia reticulata). A recently (before 2005) discovered stock close to the town of Etúcuaro is the only one known from the Río Duero subpopulation being extant, the subpopulation from the Laguna de Zirahuén has been extirpated by Black Bass. The only strongholds of the species seem to be the spring near the old mill in Chapultepec (Lago de Pátzcuaro drainage) and some springs in the Río Grande de Morelia system. Water pollution and competition through non-native fish eliminated the species from the Laguna de Yuriría and the Lago de Pátzcuaro. Eight subpopulations according to separate drainages can be distinguished: The Río Grande de Morelia subpopulation, the Lago de Pátzcuaro subpopulation, the lagunas de Zirahuén and Yuriría subpopulations, the Middle Río Lerma subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Río Duero subpopulation, the Lago de Chapala/Río Grande de Santiago subpopulation and the Río Verde subpopulation. Samplings throughout the last two decades suggest, that many of these subpopulations have disappeared and probably only the Río Grande de Morelia, the Lago de Pátzcuaro and the Río Duero subpopulations are still extant. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

Allotoca dugesii is distributed over a wide range and so we are able to distinguish several ESU's. The first one is Altdu1 and encompasses fish from the Río Duero, the Lago de Chapala and the ríos Santiago and Verde. Altdu2 is in use for populations north of the middle Río Lerma, especially the ríos Turbio and Guanajuato. The fish from the Lago de Cuitzeo basin up to the Lago de Yuriria are named Altdu3. The fourth and last ESU, Altdu4, encompasses fish from the Pátzcuaro and Zirahuén lakes.

The left map shows the Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC), the Río Lerma-Chapala (LC), the Río Lerma-Salamanca (LS), the Río Laja (LA), the Lago de Chapala (CH), the Río Santiago-Guadalajara (SG), and the Río Verde Grande (VG) basins from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, and the Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo basin (TI) from the Hydrographic Region Balsas on a Mexico map. The middle map shows the northernmost habitats, all belonging to the Río Verde Grande basin, and encompassing probably just historically inhabited watersheds as the species might be extinct there. The subbasins populated were the ríos Grande (GRA), Encarnación (ENC), de Los Lagos (RLL), Aguascalientes (AGU), Chicalote (CHI) and San Pedro (RSP) subbasins, and eventually also the ríos Teocaltiche (TEO) and Morcinique (MOR) subbasins. The right map shows the subbasins of all other basins once or still populated with this species. It occurs or occured in the whole Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basin with the subbasins lagos de Cuitzeo (CUI), de Pátzcuaro (PAT) and de Yuriria (YUR) as well as in the whole Río Lerma-Salamanca basin, including the ríos Turbio-Manuel Doblado (TMD), Turbio-Presa Palote (TPP), Turbio-Corralejo (TCO), Guanajuato (GUA), Temascatio (TEM), Salamanca-Río Angulo (SAN) and Solís-Salamanca (SOL) subbasins. Except for the lagos de Cuitzeo and Pátzcuaro populations, all the other ones seem to have disappeared. While it seems to have occured only in the Río Laja-Celaya subbasin (LAC) of the Río Laja basin, it was historically wider distributed in the Lower Río Lerma regions, where it is now also extinct in most of the watersheds. From the Río Lerma-Chapala basin it is or was known from the Río Angulo-Río Briseñas subbasin (ABR), the Río Briseñas-Laguna Chapala subbasin (BRI), the Río Duero subbasin (DUE) - still extant in the last one -, and probably also from the Arroyo Huascato subbasin (HUA). It inhabited the Laguna Chapala subbasin (CHA) and the neighbouring Laguna de San Marcos (LSM) subbasin from the Lago de Chapala basin as well as subsequent waterbodies within the Río Santiago-Guadalajara basin, namely the Laguna Chapala-Río Corona subbasin (COR), the Río La Laja subbasin (LAL), the Río Corona-Río Verde subbasin (CVE) and the Río Verde-Presa Santa Rosa subbasin (VSR). Surprisingly, the species might still be extant in remnant populations close to Guadalajara, but no more in the only watershed of the Balsas Region that this species reached, the Lago de Zirahuén subbasin (ZIR) of the Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo basin:

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Endangered/declining: „The widest ranging of the Allotoca species, historically known from much of the middle and lower Lerma and upper Santiago river basins on the Pacific slope and the endorheic Lake Pátzcuaro, Lake Zirahuén, and Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basins (Miller et al., 2005). Currently, the species is known from only six or seven locations. A new population was recently discovered in a spring along the Duero River in the Lerma River basin near the town of Etúcuaro, Michoacán, but it is very small. Recent surveys have documented the species’ dramatic reduction in the upper Santiago basin and elimination from the Zirahuén basin where it was once widespread and common. Remaining strongholds are the Molino de Chapultepec Springs in the Lake Pátzcuaro basin and La Maiza Springs in the Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia basin near the city of Morelia. Domínguez-Domínguez et al. (2002) published observations on larval feeding of this species that will be useful in the maintenance of captive populations. We recognized four ESUs based on zoogeography (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2006). Altdu1 is critically endangered and is known from the upper Santiago River basin, Lake Chapala, and the lower Lerma River basin. However, perhaps only one viable population remains, in a spring near Lake Chapala. Altdu2 is critically endangered and found at a single site in the Turbio River drainage of the middle Lerma River basin. Atldu3 is endangered and occurs at 3–4 sites in the Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basin. Altdu4 is critically endangered and known historically from the Lake Pátzcuaro and Lake Zirahuén basins. Presently, it persists only along at a heavily vegetated shoreline area of southwestern Lake Pátzcuaro and in the Molino de Chapultepec Springs, a tributary of Lake Pátzcuaro.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

Allotoca dugesii lives in lakes, ponds and streams and prefers in general depths of less than 1.3m. It can be found over clay, mud, sand, gravel and rocks. Vegetation can usually be found, but is absent sometimes. When vegetation is present, it consists of Nasturtium, Ceratophyllum, Potamogeton, Eichhornia and green algae. The currents are none to moderate, but sometimes strong, too. The water is either clear to murky or muddy.

The Bumblebee Allotoca was found on several surveys of the GWG from 2014 to 2017 in both effluents of the spring at Chapultepec, channels from about 80cm (southern-channel) to more than 1m (western-channel) width. The channels had sandy ground with gravel and several rocks on the borders. Submerse vegetation was present in form of some floating water hyacinths directly after the outlet in the south and areas with dense stocks of Egeria. Grassy riparian vegetation covered the borders and hang over the surface, the western channel was partly covered by trees. At the western outlet, some exotic Zantedeschia sp. grew along with the borders and shaded it partly. This part of the channel was densely planted with Egeria and deep to 1m. After 120m from the outlet, it was dammed, leaving the subsequent part of the channel with a varying depth between 15 and 40cm. The current in both channels was fast to moderate, the water looked characteristic milky blue, probably to some solved minerals. The vegetation in the spring itself was composed of Egeria sp. and Potamogeton sp. The water parametres taken in March 2017 were: Water temperature; 19.5°C, pH: 7.22, conductivity: 1,180μS; other fish species associated were Alloophorus robustus, Goodea atripinnis, Skiffia lermae and Allotoca diazi and Algansea lacustris.

Biology:

Meek (1904) reported young born in the last week of May and a 13mm individual taken on 27. February (water temperature 13°C) near Ejido Copalita, northwest of Guadalajara, which indicates that the reproduction may occur over a much longer period. He found females being pregnant with already eyed embryos on March the 4th (water temperature 10°C) near Undameo in the Río Grande de Morelia basin.

Diet:

The teeth are slender conical and in a double row, of which the outer is enlarged and firmly attached. Combined with observations in captivity, this leads to the assumption of a more carnivorous diet, probably hunting small water invertebrates and insects from the water surface.

Size:

The maximum known standard length is 63mm (Miller et al., 2005).

Colouration:

Allotoca dugesii is a species with a remarkable sexual dimorphism. Both sexes have the upper body olive (intermingled with silver) and the lower body silvery. The males have a dark midline from the corner of the eye to the base of the caudal fin. Females have this line partially interrupted. The base of the fins can exhibit yellow or orange colouration. Females show four to eleven dark vertical stripes with blue areas along the flanks. Bean described these stripes (in spirits) as "five or six dusky bands, the widest somewhat greater than the length of the eye. One of these bands is placed under the anterior half of the dorsal". The operculum is silvery coloured. When mating, males usually become striking orange, yellow or golden, while females display blue iridescent flankes contrasting with the dark stripes.

From at least one population (Rancho el Molino), melanistic individuals are known. Those can become totally black in both sexes, but usually display an intermediate colour pattern. Males with dark black blotches on the sides, similar to blotches seen in Skiffia multipunctata, but not so prominent, are known from several locations.

Sexual Dimorphism:

Males and females of the Bumblebee Allotoca are easy to distinguish. A safe characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Allotoca dugesii have a bigger Dorsal fin than females. The difference in colouration is clear and very distinct. Males have a dark line separating a brown back from light, sometimes silvery, belly. In breeding colours, males change the colour into a striking yellow or orange, at least on the belly, but sometimes totally. In females, the dark line separates the brown back from a striking bright blue belly with brown vertical bands separating the blue into a serious of blue vertical bands. These bands are brighter during courthip and probably used to attract males. Some females have the belly sometimes superimposed by black areas. Forms with many black dots or blotches are known as well as a melanistic, more or less completely black form, but this black markings are not gender-related. Females are a bit longer than males with a bigger and blunt head, but some experience is necessary to see these characters. Males appear a bit rectangular as a result of its bigger Anal and Dorsal fins.

Remarks:

Allotoca dugesii is the species with the widest distribution among all Allotoca, but nowadays, it seemed to have already disappeared from far more than 50% of its historically known distribution range. Last strongholds are in the Cuitzeo and Pátzcuaro lake basins. In 2010, Czech and Slovakian hobbyists have been successful in sampling this fish near Poncitlán north of the Chapala lake, so this species might still be present in some areas, where it is thought to be extinct. However, a survey trip to this location by the GWG in 2016 revealed only non-native Gambusia sp. at this location with the originally there collected Allotoca dugesii and Goodea atripinnis gone.

As a reaction on the threats this species is facing, the Austrian Association of Aquarists (ÖVVÖ) started a Studbook on this and all other Allotoca species (including the closely related Neoophorus regalis).

The Bumblebee Allotoca resembles closest Allotoca maculata, nevertheless another species, Allotoca goslinei, is recognized as the nearest relative according to several phylogenetic results. This is no real contradiction as it only means, that Allotoca maculata is the most basal representative of this genus with the dugesii-goslinei pair having evolved from a common ancestor with maculata. The other species of this genus are further apart from dugesii resulting even in the sympatric occurence of this species with Allotoca diazi in the Pátzcuaro lake basin.

Fernando de Buen described in 1940 Allotoca vivipara from the Lago de Pátzcuaro. Smith and Miller examined the Holotype and additonal material in 1987, but didn't find any significant differences between these fish and Allotoca dugesii. Therefore, they agreed with the opinion of Aurelio Solórzano (pers. comm. to Miller, 1967) that Allotoca vivipara is a synonym of Allotoca dugesii. Nowadays, there is no doubt anymore of this subpopulation belonging to Allotoca dugesii.

Husbandry:

Looking on the biotopes of Allotoca dugesii, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, rocks, roots, branches, fallen leaves and river bank vegetation. Fry is eaten in some cases, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 1.5 or 2cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 100 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With rocks and vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate or swift, specially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is not really shy, but likes to use hiding spots to observe the surrounding.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. Allotoca species can be kept down to temperatures of 15 or 16°C without problems for months, some species even lower, but this species likes it a bit warmer, so try to not deceed 17°C in winter over a longer period. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Altdu1-COR-Sant

Population: Río Santiago

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Santiago-Guadalajara

Subbasin: Laguna Chapala-Río Corona

Locality: Río Santiago, below the dam about 2.5km E of Atotonilquillo

2. Altdu4-PAT-RMol

Population: Rancho El Molino (aka Molino Viejo de Chapultepec)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Laguna de Yuriria

Subbasin: Lago de Pátzcuaro

Locality: spring at the old mill (Molino Viejo) of Chapultepec