- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

Allodontichthys polylepis

English Name:

Finescale Splitfin

Mexican Name:

Mexclapique (erronously: Mexcalpique) de escama

Original Description:

RAUCHENBERGER, M. (1988): A new Species of Allodontichthys (Cyprinodontiformes: Goodeidae), with comparative Morphometrics for the Genus. Copeia 1988 (2): pp 433-441

Holotype:

Collection-number: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Cat. No. UMMZ-213951.

The Holotype is an adult male of 42mm standard length, collected by R. R. Miller et al. on February the 23rd, 1976. With the Holotype were taken 20 juvenile and adult Paratypes of both sexes (Cat. No. UMMZ-198850).

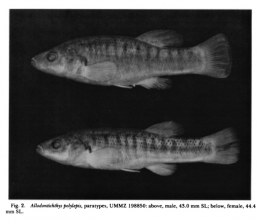

The left picture shows Paratypes of Allodontichthys polylepis, the right table compares the frequency distribution of lateral line scale counts of all four species of Allodontichthys. It shows clearly, why it bears the species epithet polylepis meaning "with many scales":

Terra typica:

The original citation from the description says, that the Holotype was caught in the Arroyo Potrero Grande (Río Ameca drainage), 9.6km east of Ameca on the road to Guachinango in the state of Jalisco. This is defintely a mistake because the type location is about the same distance west of Ameca. Maybe the spanish word for west, oeste, which is similar to east, este, caused the mistake. The Arroyo Grande or Arroyo Potrero Grande is a short creek of only a few kilometres length that meets the Río Ameca only about 6km beeline west of the town of Ameca.

Etymology:

The species name polylepis can be derived from the ancient Greek and means "with many scales", as this species has between 10 and 20% more scales in the lateral line than its congeners: πολύς (polýs = many) and λέπις (lepis = scales). Explore also the table in the chapter "Holotype".

The genus Allodontichthys was erected by C. L. Hubbs and C. L. Turner in 1939 to show the differences to the genus Zoogoneticus, "chiefly on the basis of the form of the jaw teeth, which instead of being regularly conic (everywhere evenly round in cross section) are definitely compressed and shouldered within the slender conic tip and are keeled (rather weakly) at either edge of the anterior face." The generic name is derived from the ancient Greek language. The word ἄλλος (állos) means different, ὀδόντος (ódóntos) is the genitive of ὁδούς (ódoús), the tooth. The last part of the name, ἰχθύς (íchthús, íchthýs), is the Greek word for fish, so the name of the genus can be translated into "a fish with a different tooth".

Synonyms:

Allodontichthys sp. Fitzsimons (1981)

Distribution and ESU's:

The Finescale Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal state of Jalisco, historically known only from a short (approximately 8km long) affluent of the Río Ameca, the Arroyo Grande (or Arroyo Potrero Grande, type location), from the Arroyo Estanzuela (Río de las Bolas or de la Pola) and from one of its affluents, the Arroyo de Ávalos (Arroyo Dávalos or Diábolos). The Arroyo Estanzuela is an affluent of the Río Atenguillo that again flows into the Río Ameca about 45km NNW of Guachinango. Nevertheless, the Arroyo Estanzuela collection site is separated from the Arroyo Potrero Grande collection site by approximately 300 river kilometres. Several surveys (the last one by the GWG in June 2019) since about the year 2000 indicate that the species does no more exist at the type location. From the affiliation to two different drainages, two subpopulations can be inferred: the (now possibly Extinct in the Wild) Arroyo Potrero Grande subpopulation (type subpopulation) and the Arroyo Estanzuela or Río de las Bolas subpopulation. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Allodontichthys polylepis are morphologically no differences between both populations to detect, so they are treated as only one ESU, Aldpo1. Genetically, the type population was never studied.

The left map shows the Río Ameca-Atenguillo basin from the Hydrographic Region Ameca on a Mexico map. Within the Río Ameca-Atenguillo basin, the Finescale Splitfin historically occured in two subbasins, shown on the right map: The Río Ameca-Pijinto subbasin (PIJ), where it is now probably extinct, and the Río Atenguillo subbasin (ATE), where it still occurs in low numbers:

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Critically Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Critically Endangered/declining: „As of its initial description in 1988 (Rauchenberger, 1988), this species was known from three locations in the upper Ameca River basin. By 2000, the Potrero Grande Stream population had disappeared for unknown reasons, but the populations in the De la Pola River (reported as Bola by some collectors) and its tributary the Dávalos Stream (reported as Diábalos by some collectors) had persisted (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005). These two populations have declined since then, and an intensive 2016 survey yielded only a single individual from each water body.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

The Finescale Splitfin lives in clear creeks and streams with riffles and pools over substrates of sand, gravel, rocks, boulders and some silty mud. The vegetation comprises green algae on rocks or floating. The currents were slight to none in the dry season, the depths usually less than 0.5m. Like all known Allodontichthys-species, the Finescale Splitfin is a bottom-dwelling and riffle-inhabitating species. Its habitats are similar to those of the North American darters (Percidae, genus Etheostoma) living among and under rocks in shallow waters.

A GWG survey in February 2016 (dry season) revealed the habitat at the Arroyo de Ávalos exactly like it was given by Miller in 2005 (see above). There was only little current and the creek itself has partly shrinked to pools. In one of this pools, the group was able to find a single male of the Finescale Splitfin among several Ilyodon furcidens and Tilapia. The fish was hiding next to a big rock in about 80cm deep water. The Arroyo Estanzuela was that time a middle sized river with rocky areas alternating with sandy sections. The species was found in the current between rocks and in deep pools under the bridge next to La Estanzuela over sand and gravel. A second GWG survey to this river in November 2018 was not succesful in finding any fish due to a broken electrofishing device and too much water (rainy season). A survey in June 2019 also failed when the river was nearly dry with just a few but deep pools left.

The left picture down here of the Arroyo Estanzuela from June 2019 was taken from the same point as the third picture above from March 2016 and shows in comparison dramatically how much the water level can change during the year and with what kind of problems the Finescale Splitfin has to deal in the dry season. Two more pictures show the same river from another point in November 2018 (rainy season, left) and June 2019 (dry season, right).

Biology:

Mary Rauchenberger noted, that none of the collections she used for her description (collected in March 1957, February 1970 and 1976) contained gravid females, but Miller (2005) reported small young and gravid females from late February to early March.

As the GWG surveys so far found only very few adult or semi-adult specimens at one occasion, we not dare to add anything to the reproduction periode of this species. However, we think that it helps to compare this species with its congeners and also observations in aquariums make us believe, that there is not much difference to find. Looking on the so far seen habitats make us assume, that it has a comparable life history to Allodontichthys zonistius as well.

Diet:

The diet is probably the same as from related species like Allodontichthys tamazulae, where Miller found large insect larvae in its guts. In general, Allodontichthys species have short guts (0.67 - 1.20% of the total length) and (except in A. hubbsi) the outer-jaw teeth shouldered or "incipiently tricuspid".

Size:

The maximum known standard length is 50mm (Miller et al., 2005).

Colouration:

Here the original citation by Mary Rauchenberger, 1988: "In ethyl alcohol, the body is dark brown dorsally, lighter on the ventral half of flanks and cheek; dorsolaterally, edges of scale pockets are blackened, giving a flecked appearance; scapular blotch dark and prominent; 8 – 11 medium brown vertical bars from behind the pectoral fin onto the caudal peduncle; lateral bars may be obscured by a general darkening in larger males; dorsum with irregular spotting in juveniles and females; pectoral and pelvic fins relatively pale; dorsal fin in fish 20 – 40mm with a basal row of spots followed distally by 1 or 2 more irregular rows of larger spots; spotting in dorsal and anal fins sometimes obscured in larger fish, especially males, by dusky-dark pigmentation on basal three-fourths of the fin."

In life, the colouration can be stunning. Males show an into several bars broken dark lateral line, the prominent black scapular blotch underlined by a striking yellow blotch and overlined by a striking blue one. The body colour changes from a greyish-whitish pink into greyish green on the back or even turquise. Several black blotches in the dorsal fin are forming few irregular vertical zones. From the dorsal fin backwards, the upper half of the body shows a change of black zones and striking greenish areas. The fins sometimes show yellow or at least become yellowish on the bases. The area behind the scapular blotch shows a zone of black bars underlayed by a blue or bluish green mirror. Dominant males may show an additional intense orange or a reddish coloured peduncle contrasting with a dark grey caudal fin. The females are coloured similar, but do not show these striking greenish or bluish zones except the scapular blotch. Backwards from this blotch, the females show a yellow zone.

Sexual Dimorphism:

At first appearance, males and females of the Finescale Splitfin are not as easy to distinguish from each other as sexes from other species of Goodeids, but easier than males and females from closer related species like Allodontichthys hubbsi or zonistius. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Allodontichthys polylepis have a much bigger Dorsal fin than females, and it is usually more intensively coloured and blotched. A third character is the colour: males are brighter coloured with the upper part of the body clearly separated from the lower part by a series of black blotches forming an irregular line and sometimes (depending on the location) shiny areas on the back while females don't have any shiny areas on the back and are duller coloured. On the other hand, females have usually its Anal fin coloured more intensively yellow than males.

Remarks:

The Finescale Splitfin was discovered in 1957 by R. R. Miller & M. Miller in the Arroyo Estanzuela (Río de las Bolas), a tributary of the Río Atenquillo (Río Ameca basin). However, it took scientists more than 30 years to describe this species. Its habitats are distant in distribution with respect to its congeners, making it to the only known representative aside the ríos Armería and Coahuayana-basins.

The fatal decline of this species seemed to have happened by the end of the last century. The population from the type locality, the Arroyo Potrero Grande, disappeared in the late 1990's, probably through competition by Green Swordtails, an invasive species that appeared at this location about that time, and water pollution. The last confirmed collection for the Río de las Bolas (before 2016) dated back to 1998, when Brian Kabbes, who thought he had been visiting the type location, but indeed had been at the Río de las Bolas, reported the species from deep pools in the nearly dried out river next to the town of La Estanzuela in December 1999. The population in the nearby Arroyo de Ávalos was thought of having existed at least until 2001 until a major drought dried the creek completely between 2001 and 2003 and reduced the waters of the Río de las Bolas to some pools without current. However, such drought events also had happened in the past (Domínguez-Domínguez, pers. comm.). All in all, the reasons for the seeming disappearance of Allodontichthys polylepis in the wild are not completely understood, but is thought to have its roots in this series of droughts. Until 2016, the Finescale Splitfin was thought to be Extinct in the Wild.

In 2008, O. Domínguez-Domínguez started a semi-captive conservation program with the help from the Fish Ark Mexico Project. An artificial pond on the area of the Botanical garden of the Faculty of Biology from the University of Morelia was built and stocked with Neotoca bilineata and Zoogoneticus tequila in April, as well as with Allotoca goslinei and Allodontichthys polylepis in August. In contrary to the other three species, all catches in the years thereafter did not reveal any specimen of the Finescale Splitfin and so it obvious, that this program failed.

The species was brought to Europe by the Austrian A. Radda in 1987. His friend, late H. Stefan, bred this fish over years and distributed it to several people with the location given as "Río Potrero Grande", so the type location. This dedication was taken over by the GWG, but in 2019 first doubts occured when pictures from the Austrian aquarist, late O. Böhm, in the Aqualog-magazine were labeled with "A. polylepis, Río Estancuela" and "A. zonistius, Río Estanciela". The second determination was definitely wrong, but all the pictures showed clearly the stock distributed in Europe. Taking in consideration that B. Kabbes in 1998, following Raddas words, also went to the Arroyo Estanzuela thinking he was as at the type location, it might have happened, that A. Radda went erronously to the wrong location when collecting the fish. However, studies of literature in the near future might help to bring clarity to the situation, but for the moment, we treat both in aquariums distributed stocks as being from different locations to prevent mixing them up. This has direct influence on the Allodontichthys polylepis conservation project: In 2011, the number of Allodontichthys polylepis in captivity from both locations encompassed only about 30 or 40 specimens and it was said to be the rarest fish in the world. The number of individuals from the type location went down to eight adults and a handfull of juvenile fish, and from the Río de las Bolas population, there were only three females kept with a dozen of young fish they had been given birth to. Thereafter, the GWG and the Aqualab in Morelia started a breeding and distribution program with this species. Four years later in 2015, the species was still very rare but no more in immediate danger of extinction, encompassing a few hundred fish from the Río de las Bolas and nearly two hundred from the Arroyo Potrero Grande. In 2017, the number of fish from the type location had increased again up to about 350, the number of fish from the Rio de las Bolas was stable at about the same number. Almost all individuals of both populations are part of a breeding program including zoos and hobbyists and run by the Haus des Meeres - Aqua Terra Zoo in Vienna. Property, distribution, membership and more details are strictly regulated to be most successful in increasing the number of fish.

A survey of the GWG to the habitats of Allodontichthys polylepis was successful in finding this species again in 2016 in the Arroyo de Ávalos (after 13 years disappearance) and in the Río de las Bolas at La Estanzuela (after maybe 17 years), but not at the type location in 2018 and 2019. However, even when the species is absolutely rare in the wild, there is obviously still a small, but fertile population left that gives hope, that the species may survive in the wild.

Husbandry:

Looking at the biotopes of Allodontichthys polylepis, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, rocks and boulders. As there is quite a lot of aggression between the adult fish, the tank set up should prevent the fish from seeing each other all the time. Fry is eaten in some cases, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 2 to 2.5cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 150 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With rocks well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate or swift, especially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with the same food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. It feeds well from flake food, tablets and granulate, hunts greedy for Nauplia of Brine Shrimps and even takes flesh of mussels. This species isn't shy at all.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So, mainly for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or gets too warm (25°C).

This species is doing very well when kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Aldpo1-ATE-RBol

Population: Río de las Bolas (aka Río de la Pola, Arroyo or Río Estanzuela)

Hydrographic region: Ameca

Basin: Río Ameca-Atenguillo

Subbasin: Río Atenguillo

Locality: Arroyo Estanzuela, at bridge E of Estanzuela