- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

Allodontichthys hubbsi

English Name:

Whitepatch or Whitepatched Splitfin

Mexican Name:

Mexclapique (erronously: Mexcalpique) de Tuxpán

Original Description:

MILLER, R. R. & T. UYENO (1980): Allodontichthys hubbsi, a new species of Goodeid fish from Southwestern Mexico. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology University of Michigan No. 692: pp 1-13

Holotype:

Collection-number: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Cat. No. UMMZ-200221.

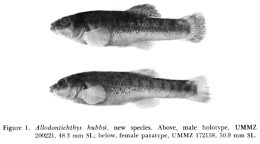

The Holotype is an adult male of 48.3mm standard length, collected together with 14 Paratopotypes (Cat. No. UMMZ-172153) of 22-44mm by R. R. Miller and J. T. Greenbank on March the 8th, 1955. Among several collections of Paratypes from different locations, 14 specimens (29-61mm) were collected at the Río Tuxpan at the HW 110 bridge, 4.8 km S of turnoff to Ciudad Guzmán, same date and collectors (Cat. No. UMMZ-172158).

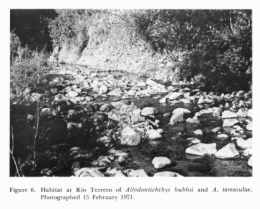

The left picture shows the types of Alldontichthys hubbsi, the right one the Río El Terrero in 1971, where R. R. Miller and T. M. Cavender collected 45 Paratypes of this species:

Terra typica:

Etymology:

Citing Miller and Uyeno in the original description: "The species is named after the American ichthyologist Carl L. Hubbs (1894-1979), whose early studies on Goodeids set the stage for subsequent understanding of this compact but highly diversified family."

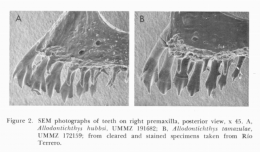

The genus Allodontichthys was erected by C. L. Hubbs and C. L. Turner in 1939 to distinguish this genus from the genus Zoogoneticus "chiefly on the basis of the form of the jaw teeth, which instead of being regularly conic (everywhere evenly round in cross section) are definitely compressed and shouldered within the slender conic tip and are keeled (rather weakly) at either edge of the anterior face." The generic name is derived from the ancient Greek language. The word ἄλλος (állos) means different, ὀδόντος (ódóntos) is the genitive of ὁδούς (ódoús), the tooth. The last part of the name, ἰχθύς (íchthús, íchthýs), is the Greek word for fish, so the name of the genus can be translated into "a fish with a different tooth".

Synonyms:

none

Distribution and ESU's:

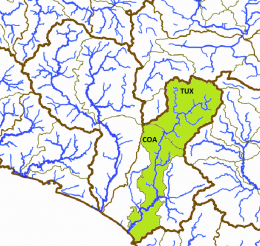

The Whitepatch Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal state of Jalisco, historically known from the Río La Trampa (called Arroyo San José de Tule by some authors, type location) and the Río El Terrero, both belong to the Río El Tule drainage, and from the Río Tamazula and further downstream from the upper and middle Río Tuxpan, both names for consecutive sections of the Río Coahuayana, to at least 45 river kilometres below the town of Tuxpan. Furthermore, the distribution encompasses - as far as we know - three affluents of the Río Tamazula: a nameless creek east of La Garita, the Río San Jeronimo and the Río Contla. Though the Río El Tule is an affluent of the Río Naranjo, the name for the river section of the Río Coahuayana following the Río Tuxpan, the Arroyo San José de Tule and the Río Tuxpan collection sites are separated by several cascades and 300m in altitude. From the affiliation to two different drainages, two subpopulations can be inferred: the Río El Tule subpopulation (type subpopulation) and the Río Tuxpan subpopulation. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered. The species is usually associated with its congener Allodontichthys tamazulae.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Allodontichthys hubbsi, it is possible to distinguish two different ESU's, according to the two different subpopulations. Aldhu1 encompasses the northern populations of this species from the Río Tamazula and its affluents like the Río Contla and a nameless creek east of La Garita, and populations down the course of the Río Tamazula and the following river section, the (upper) Río Tuxpan, where Miller collected in 1955. The second ESU is named Aldhu2 and this abbreviation is used for the south-eastern populations north of Pihuamo (ríos El Terrero and La Trampa). Fish of the type location and areas in the geographic vicinity of it belong to this ESU.

The left map shows the Río Coahuayana basin from the Hydrographic Region Armería-Coahuayana on a Mexico map. Within the Río Coahuayana basin, the Whitepatched Splitfin occurs in two subbasins: The Río Tuxpan subbasin (TUX) in the Río Coahuayana headwaters and the Río Coahuayana subbasin (COA) further downstreams, both shown on the right map. Aldhu1 is known from both the ríos Tuxpan and Coahuayana subbasins, Aldhu2 only from the Río El Tule drainage in the northeastern part the Río Coahuayana subbasin:

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Endangered/stable: „This species is known from only six areas in the upper Coahuayana River basin (Lyons and Mercado-Silva, 2000). We recognized two ESUs based on genetic analyses (Domínguez-Domínguez, unpublished data). Aldhu1 is endangered and occupies four areas of the Tamazula River drainage, short segments of the Tamazula River, the San Jerónimo River, a small unnamed tributary of the Tamazula, and the Contla Stream. The Contla Stream had the best population with several hundred adults. Aldhu2 is critically endangered and has small populations in three tributaries of the Coahuayana River that are isolated from the Tamazula River by waterfalls, San Jose del Tule Stream, El Terrero Stream, and Pihuamo River. A 2019 survey found dozens of individuals in the San Jose del Tule, a single individual in the El Terrero, and none at the one site sampled on the Pihuamo."

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

Like all known Allodontichthys-species, the Whitepatch Splitfin is a bottom-dwelling and riffle-inhabitating species. As expected from this behaviour, Miller & Uyeno found a considerably smaller swim bladder than in Ilyodon. It extends only to between the fourth and fifth rib (versus to the first in Ilyodon). The fish live around and under stones and boulders of rocky riffles of generally clear streams, usually from 3 to 8m wide (up to 30m in the main stream Río Tuxpan, where it is said to be scarce). It is associated with abundant green algae on rocks and along stream margins, often with trees (including Salix) shading part of the habitat. The currents are moderate to fairly swift in the dry season and torrential during the wet summer months. Its habitats are similar to those of the North American darters (Percidae, genus Etheostoma) living among and under rocks in shallow waters. At the Río El Terrero, the long rocky riffles are separated by pools up to 8x20m in major dimensions. Miller found the water clear, but quite easily muddied because of the silt amongst the rocks and boulders. He described the water temperatures on several visits to the Río Terrero and to the type locality varying from 18 to 22°C, with the air temperature generally higher (24-28°C). The depth of the water varied from 2.5 to 0.15m.

On a survey in 2016, a group of members of the GWG found this species together with Allodontichthys tamazulae and Ilyodon whitei close to the bridge at Contla in the Río Contla in very shallow (about 20cm deep) water in swift current. Both Allodontichthys species were easy to catch by lifting rocks (where the fish were hiding below) and putting a dipnet over the place. The river had a width of about three to four meters in this dry season, the broad pebbly river bank suggested a width of about eight to ten meters in the rainy season, which could be confirmed on a second survey in November 2018. The first survey revealed good stocks of this species with nearly the same number of individuals as of the Peppered Splitfin. The group was able to find this fish additionally in the Río Tamazula at the east end of the town of Tamazula de Giordano, together with the same species of Goodeids and "Xenotoca" lyonsi in sligthly deeper water and swift current. On the second survey of the Río Contla in November 2018, it was a murky fast flowing river, wide up to 8 or 10m and deep to 120cm at some places. Only few Whitepatched Splitfins could be found this time, including fry (and two female "Xenotoca" lyonsi). A survey of the Río La Trampa in the same month revealed the species above the town of San José de Tule near the aquaeduct, whereas in the town, close to the type locality of the Whitepatch Splitfin, only Allodontichthys tamazulae could be found. All Allodontichthys at all surveyed locations in November were in poor health condition probably due to a higher pressure through parasites. A survey of the GWG to the Río Coahuayana drainage in March 2019 revealed the species in the whole Río Tamazula course from about Tamazula town up to river sections above El Tulillo, also in the creek at La Garita, the Río San Jeronimo from about Vista Hermosa up to almost the Turbinas de La Cruz, in the Río La Trampa and a single male in the Río El Terrero W of 21st de Noviembre. The species was in most of the locations quite abundant. The so far last survey in June 2019 found this species also in the middle Río Tuxpan about 45 river kilometres SW of Tuxpan, where it was quite abundant.

Biology:

The species is probably sparsely distributed in riffle habitats. It was found to be abundant at Contla in February 2000 (John Lyons) and March 2016 (GWG), as well as in the ríos San Jeronimo, Tamazula, Tuxpan and La Trampa in March and June 2019 (GWG). In the original description, Miller noted that in aquarium observations by Dolores Kingston, this species showed an aggressive behaviour with males killing each other and females when confined to small aquaria. He postulated that this indicates this species is solitary. He observed a peculiar swimming of juveniles (that differed from the sympatric congener A. tamazulae) in riffles at the Río El Terrero that resembled a slow-moving tadpole. They hugged the bottom, hovering close to rock surfaces. He saw no adults there, so he thought, they may not venture far from rock cover much of the time. Surveys of the GWG to the Río Coahuayana drainage in March and June 2019 found at almost all collection sites gravid females in different stages and fresh born fry.

GWG surveys in 2019 found this species in contrast to its congener Allodontichthys tamazulae mainly under big rocks and boulders (The Peppered Splitfin was easier to find within riparian vegetation and roots on the river bank), which might give a hint why it is possible for both species to co-exist (different habitat and/or food preference?). A batch of fry again was found hiding in a bunch of a Potamgeton-species with thin leaves in very shallow water (5cm) close to the river bank. An underwater film taken in the Río La Trampa in March 2019 revealed only few individuals hoovering beneath foliage and roots on the bottom of the river, while Allodontichthys tamazulae could be seen in bigger numbers almost afloat in the current.

A survey of the GWG in 2016 found a decent number of hellgrammites, huge larvae of Dobsonflies (subfamily Corydalinae, family Corydalidae, order Megaloptera) covering in the mud of the Río Contla and hunting for fish, especially Ilyodon, but for Allodontichthys as well for sure.

Diet:

The tricuspid and pointed fork-like teeth and the short gut indicate carnivorous feeding habits. The examinations of Turner found the guts of the related Allodontichthys tamazulae containing large insect larvae. In general, Allodontichthys species have short guts (0.67 - 1-20 % of the total length). Compared with all other respresentatives of this genus, the tricuspid teeth of the Whitepatch Splitfin are obviously stronger forked, so maybe they are better adapted to capture animalistic prey like Mayfly-larvae, Amphipods or Bloodworms.

The left picture compares the upper jaw of Allodontichthys hubbsi (left) with tamazulae (right). It can be seen, that the jaw and teeth are oriented more horizontally in hubbsi, so eventually this species feeds in a different way than tamazulae (it may allow the species to go deeper between rocks and gravel to pick up the bait). The right picture shows a shrimp of the genus Macrobrachium. Juveniles of these common decapods would be a good food source for Allodontichthys-species.

Size:

The maximum known standard length is 61mm (Miller et al., 2005).

Colouration:

Citing Miller and Uyeno: "In preservative (ethanol), the dorsal fin of males has 3 to 5 irregular rows of dark spots, often strongly developed, that extend from near the base to well out onto the fin. The other fins are clear. There are as many as 9 to 11 bars on the upper half of the body that are broad and distinct posteriorly but become narrow and irregular in advance of the dorsal fin; they are more conspicuous in smaller males. The bars are often disrupted between back and midside to form lateral spots or blotches, especially in smaller males; in these specimens the back has a strongly mottled appearance. Barring is often indistinct in larger males. Females have 1 to 3 irregular rows of dark spots, generally along the lower half of the dorsal fin, that are usually less conspicuous than those in the male. The other fins are clear except that one fish shows a few, weak dark dashes on the interradial membranes of the caudal fin near its midbase. There are 5 to 8 irregular bars, blotches, or spots along the midside, from caudal base to about dorsal origin, that are generally discontinuous with the irregular barring and spotting on the back. In smaller females and juveniles there is a tendency for the spots along the midside to coalesce into a lateral stripe.

In both sexes there are narrow to broad dark crescents outlining the posterior margins of the scales along the upper sides, most prominent in males. Near the midside and slightly below, dark pigment tends to be centred on the scales to form irregular longitudinal rows of spots. The lower sides and venter are light. A prominent, dark scapular bar or blotch, often crescent-shaped, occurs above and just behind the base of the pectoral fin in both sexes. In life, no bright colours were noted."

Sexual Dimorphism:

At first appearance, males and females of the Whitepachted Splitfin are not very easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Allodontichthys hubbsi have a bigger Dorsal fin than females, and it is usually more intensively coloured. A third character, but only visible when fish are feeling safe and relaxed, is the colour: males are brighter coloured with the upper part of the body clearly separated from the lower part by a series of black blotches forming an irregular line. Females are coloured duller with the upper from lower part of the body not so clearly separated.

Remarks:

This is the only Goodeid species and one of only few known fish species at all with multiple sex chromosomes, 2n = 41 in the male and 2n = 42 in the female (Miller & Uyeno, 1972). Both authors thought of the sympatric congener Allodontichthys tamazulae to be the closest relative, but later phylogenetic results (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and mitochondrial control region, Webb, 2002) and morphological features (Rauchenberger, 1988, e.g. it differs from its congeners having only 3-3 versus 4-4 mandibular pores in the acustico-lateralis system, a longer base of the anal fin and the dorsal fin placed more anteriorly) heavily supported the position of Allodontichthys hubbsi at the basis of the genus as the most distinct representative. Latest phylogenetic studies (Cytochrome b gen, Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2011) however place the Whitepatch Splitfin again next to Allodontichthys tamazulae as its closest relative. Nevertheless some inconsistencies remain: How is it possible, that two species of one genus prefering similar habitats evolve in one river system, and how can it happen, that both persist next to each other? Here the emergence of different sex chromosmomes in Allodontichthys hubbsi could be the answer. But how can the morphological distinct features between hubbsi and its three congeners be explained? Maybe the relationship is not that narrow and the Whitepatch Splitfin is really the most basic species of Allodontichthys, but former hybridisation processes between Allodontichthys hubbsi and tamazulae may be pretending narrow relationship in the cytochrom b gen. Including several nuclear genes in phylogenetic studies migth bring an answer, but for the moment, the position of the species in the genus Allodontichthys is not clearly resolved.

The Whitepatched Splitfin occurs in most of the habitats sympatrically with Allodontichthys tamazulae. It is very likely, that both species are ecologically niched with Allodontichthys tamazulae prefering dense root mesh of trees and riparian vegetation where it regularly could be sampled on surveys in 2019 and Allodontichthys hubbsi hiding under big rocks and boulders in the river course. For decades it was thought to be absolutely rare and it seemed it had been replaced almost completely by Allodontichthys tamazulae. Allodontichthys hubbsi was said to be restricted to the upper Río Coahuayana basin and reported from only six sites (Lyons & Mercado-Silver, 2000). In total, only 264 specimens have been sampled for Museums throughout the last six decades. From the Río Tuxpan were reported 14 individuals out of 1955, in 1964 and 1969 only A. tamazulae was found. A tributary to the Río Tamazula northeast of the city of Tamazula de Giordano revelealed also only the Peppered Splitfin in 1978, though in 1955 there were at least a few Whitepatch Splitfins (two individuals collected). From the Río El Terrero were reported 84 A. hubbsi in collections from 1970 to 1976, but no more thereafter until 2019. Last surveys (2019) revealed several so far unknown extant populations in the course of the Río Tamazula/Tuxpan including the ríos San Jeronimo and Contla and in the Río El Tule system and the number of individuals in the rivers being much bigger than known before. It is not fully clear, if the low numbers in old collections are connected with different methods in collecting (dipnet versus electrofishing e.g.), or if the numbers really were that much lower, which would raise the question, what makes the species nowadays to prosper that well.

J. Lyons and N. Mercado-Silva (2000) wrote, that in the field, the easiest possibility to distinguish A. hubbsi from tamazulae is by the colour of the back. While the Peppered Splitfin shows black or brown spots, the Whiteptach Splitfin doesn't have clear markings. Mary Rauchenberger (1988) described the dorsal body pigment of A. hubbsi as reduced in places, giving the fish a blotchy appearance. Additionally, she remarked pale fins in contrast to the other species.

The left picture is showing the backside of several Allodontichthys hubbsi and a single Allodontichthys tamazulae, the right one compares the lateral view of Allodontichthys tamazulae (above) and hubbsi (below):

Husbandry:

Looking on the biotopes of Allodontichthys hubbsi, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, rocks and boulders. Some breeders observed a higher level of aggression between the adult fish, so the tank set up should prevent the fish from seeing each other all the time. Fry is eaten in some cases, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 2 to 2.5cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 150 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With rocks well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate or swift, especially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy and the species is not acting shy at all.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species may do very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier..

Populations in holding:

none