- HOME

- ABOUT US

- ABOUT GOODEIDS

- GOODEID SPECIES

- PLAN G

- ABOUT PROFUNDULIDS (in development)

- PROFUNDULID SPECIES (in development)

- LINKS

- DONATIONS

Zoogoneticus tequila

English Name:

Tequila Splitfin

Mexican Name:

Picote tequila

Original Description:

WEBB, S. A. & R. R. MILLER (1998): Zoogoneticus tequila, a new goodeid fish (Cyprinodontiformes) from the Ameca drainage of Mexico, and a rediagnosis of the genus. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology University of Michigan Ann Arbor 725: pp 1-23

Holotype:

Collection-number: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Cat. No. UMMZ-233655.

The Holotype is a mature male of 26.7mm standard length, collected by R. R. Miller and J. T. Greenbank on March the 25th, 1955, and originally identified as Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cat. No. UMMZ-172224). Paratypes were two immature females of 25.4 and 28mm standrard length, collected with the Holotype (UMMZ-233656), and several aquarium-reared descendants of fish collected by M. Smith. C. Rodriguez, L. Butler and D. Lambert on February the 26th, 1990.

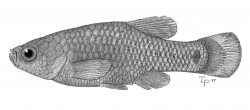

The left picture shows a drawing of the male Holotype of Zoogoneticus tequila:, the right one the typical round pyramids of the Guachimontones archaelogical site, probably the most important one of the Teuchitlán culture. The history of the people of this region and the fate of the fish they were collecting for food was always closely linked, that's why the story of the Tequila Splitfin is also told in the Guachimontones Museum at the archaelogical site. The photo shows the town of Teuchitlán next to the Presa La Vega, so the type location of this species ist just a 500m away from the pyramids:

Terra typica:

The Holotype was collected in the Río Teuchitlán, at the east end of the town of Teuchitlán in Jalisco.

Etymology:

This species is named for the Mexican Volcán de Tequila, which looms north of the type locality.

The genus Zoogoneticus was erected by Meek in 1902 with quitzeoensis as type species with reference to the fact that this genus encompasses livebearing fish. The generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek with ζῷον (zóon) meaning animal, γόνος" (gónos) offspring and νέμω (néon) in the sense of distributing. The Latin suffix -ticus forms a noun from an adjective, so the name of the genus means something like "baby distributor".

Synonyms:

Zoogoneticus sp. Lambert, 1990

Distribution and ESU's:

The Tequila Splitfin is a freswater fish species endemic to the Mexican federal state of Jalisco. It was historically only known from the type localiy, the Río Teuchitlán in the Río Ameca headwaters and already thought to be Extinct in the Wild while it had been described. Only one time later, a single male individual was seen at the El Rincón spring in 1999 (Kabbes, 1999). Another location close by the type location was detected in 2001 (de la Vega-Salazar et al., 2003), but reported as extinct in 2013 (Domínguez-Domínguez, pers. comm.). The species is actually (2019) and since 2016 in a process of reintroduction at the type location (Herrerías-Diego et al., 2016; Medina-Nava et al., 2017; Domínguez-Domínguez, 2017). As known only from the type location, the Río Teuchitlán, no subpopulations are distinguished. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Zoogoneticus tequila, there are no different populations known, so the only ESU for this species is Zoote1

The left map shows the Presa La Vega-Cocula basin from the Hydrographic Region Ameca on a Mexico map, the right map the Río Salado subbasin (SAL):

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Extinct in the Wild/last record 2008: „This species, endemic to the Teuchitlán Springs in the upper Ameca River basin in the state of Jalisco, was thought to be already extinct in the wild when it was formally described in 1998 (Webb and Miller, 1998; Miller et al., 2005). However, in 2000, a tiny remnant wild population was discovered in a small and isolated area of the Teuchitlán Springs (De la Vega-Salazar, 2003; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005, 2008). This population was so small (< 100 individuals) that it was already inbred (Bailey et al., 2007). The last collection from there was in 2008. A major drought in 2010 completely dried the habitat of Z. tequila, and when the drought ended and water levels increased, the area was invaded by the non-native Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Poeciliidae), a species that has been associated with the decline of several goodeid species. Many efforts to find Z. tequila were undertaken after 2010 without success and eventually the species was declared truly extinct in the wild. Fortunately, captive populations are relatively common in Mexico, the United States, and Europe. In 2014, faculty, students, and staff at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nícolas de Hidalgo, in Morelia, state of Michoacán, began a project to re-introduce captive stocks of Z. tequila into the Teuchitlán Springs. They exposed the captive fish to semi-wild conditions in outdoor ponds for several generations and then in 2016 added pond fish to a different semi-isolated area of the springs from which nearly all non-native species had been removed. Thus far the stocked fish are surviving and reproducing. However, continued monitoring and removal of non-native species will probably be required to ensure that Z. tequila persists in the Teuchitlán Springs.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

The original type habitat was a shallow and open lake like expandation of the Río Teuchitlán, 8m in diameter and 1.3m deep. The species prefered depths of less than 1m. The substrates were mainly mud and silt, a few rocks and sand were present. The currents were none to moderate and the water warm (about 26°C in March) and continuously turbid by cattle, pigs and horses. Few plants were living there: Eichhornia, a broad-leaved Potamogeton and a hyacinth-like plant. The species disappeared from there at the beginning of the 1990's. Regarding the rediscovery of the species go to "Remarks".

Biology:

There is not much known about this species in the wild, due to its fast disappearance. Webb and Miller determined, that both sexes become mature within ten weeks when kept by 26-28°C. This could take more time in the wild with lower temperatures. Broods numbered as many as 20 - 29 offspring, fewer than 10 in the first year.

As there is no information available about the life of this species in the wild, we only can gather informations by looking on related species, means Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis and purhepechus. Observations in November 2014 (Köck, Artigas-Azas, Valdés-Gonzáles, Radax, Davies and Hunter) on Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis in lagos Zacapu and Cuitzeo revealed this species living there within dense vegetation of reed or Taxodium roots. In these habitats, it would have been no difficulty to sample hundreds of fish of different sizes in half an hour. In the manantial la Mintzita, the same species could be found between large rooks and dense vegetation (Elodea or Egeria) as well as between the stems of water-lilys. Also here, a group of GWG members was colleting and sampled dozens of fish of different sizes in a few minutes. In the manantial La Luz and Lago de Camécuaro, Köck, Davies, Radax, Hunter and Betancourt collected Zoogoneticus purhepechus in November 2014. In the Lago de Camécuaro, the species was hiding between Taxodium roots similar to the sister species in Zacapu, whereas the same species was hiding between rocks and reed at La Luz. In all habitats, different stages of juvenile fish as well as adult fish and even gravid females could have been collected easily with hand nets.

Diet:

Conical teeth and a rather short gut suggest a carnivorous feeding behavior. Combined with a small mouth, this species is definitely a predator, probably picking small invertebrates like crustaceans and insect larvae in the wild.

Size:

The maximum known standard length is 48mm (Miller et al., 2005).

Colouration:

Adult males are dark olivaceous on the sides, back, nape and top of the head. Mottling is present on the side of the body, which often has a greenish hue. Many of the lateral scales are reflective, producing iridescense. The colour fades to pale yellow below the lateral scale series on the belly and below the eye. There is a pair of spots, which usually coalesce, at the base of the caudal fin. The mottling and the basicaudal spots may not be visible during breeding condition, when the body is darkest, nearly black. The unpaired fins are dark, fading towards the margins, with the pigmentation concentrated along the lengths of the rays. The greenish cast of the body can occasionally be seen in the dorsal and anal fins. The borders of the dorsal and anal fins have a thin cream-coloured band. The caudal fin has a broad subterminal red to orange band, and the region proximal to this band is heavily melanized. The pelvic fins occasionally show some terminal cream colouring, but the pectoral fins are unpigmented. Females are olivaceous. The sides, back, nape and top of the head are dark and display mottling, while the belly below the lateral series and the area below the eye are pale yellow. Two to four large spots are found on the ventral half of the caudal peduncle. These spots occasionally fade in older individuals. A pair of basicaudal spots, which typicaly coalesce, are visible in most specimens. The unpaired fins may be dusky, but are not dark, and do not possess the cream-coloured margins that males display. Occasionally large females show a thin subterminal band of red-orange in the caudal fin, but it is less intense than in males. The unpaired fins are clear.

Sexual Dimorphism:

Males and females of the Tequila Splitfin are easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, males typically have an white to creme coloured terminal band on dorsal and anal fins while females display clear fins. The most striking character is the broad yellow or orange terminal band on male caudal fins. Males are at least during courthsip dark coloured which contrastes nicely with few shiny scales, while females might keep their female colouration.

Remarks:

A single male of the Tequila Splitfin was sampled in 1955 by Miller and Greenbank, but identified erroneously as Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis, with which species it was collected and found sympatrically (UMMZ 172224). Many years later, the mistake was detected, the fish identified as a new species and finally, 43 years after the first capture, described by Webb and Miller.

In 1955, when the fish was taken first, all of the fish at the type locality were abundant, including Skiffia francesae (though the water was turbid by a lot of domestic animals). In 1990, it still was present (also Allotoca maculata) whereas Skiffia francesae had disapperared. Several exotic species had been introduced in the habitat. Since 1992, collections have been unsuccessful. Intensive sampling in 1996 failed to reveal any Goodeid in the type locality. So it took humans not even 40 years to extirpate consequently all species of Goodeids in only one habitat.

Brian Kabbes detected a young but mature male in the Balneario El Rincón in 1999, which gave hope, that the species was still existing there, but no more individuals were seen therafter.

In 2001, a wild population of this species was rediscovered in a very small spring pool (3 x 4m in diameter). The population there was composed of only a handful of adult fish and a few tens of juveniles (De la Vega-Salazar et al., 2003). In 2007, N. W. Bailey et al showed, that the allelic richness of this population (though it was comparable in size to an aquatic stock) was higher than in any aquatic stock. In 2013 the loss of this population was reported (pers. comm. Domínguez), so there is not much hope that this species is still persisting in the wild.

This species has been used by A. Arbuatti and P. Lucidi to survey, wether the environmental structure of a tank leads to a change or loss of behavioral richness. Due to the fact, that differences have not been found between enriched tank set ups and natural structures, this study encourages the breeding under captive conditions to conserve this species for a later reintroduction in the natural environment.

The Goodeid Working Group, Chester Zoo and other organisations started together with the University of Morelia a reintroduction project for this species (and the critically endangered cyprinid Notropis amecae) in 2015. This project encompasses strategies to get the local residents on board, the using of recreation ponds for the acclimatation of captive bred fish, the reintroduction of the fish and a monitoring and scientific guidance over 2 years. The whole project is thought to go over four years and would have been the first reintroduction project done with a Goodeid species. Here can be read the details of the project in 2016.

Husbandry:

Looking on the biotopes of the related species Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis and purhepechus, they suggest Zoogoneticus tequila may also prefer dense vegetation and roots to hide. In the wild, there was little or none current to observe in the biotops of these species, so it won't be necessary in the aquarium as well. In the aquarium, the fish often hide deep in the shelter, but courting or impressing as well as fighting males can often be seen in the open water. Fry is rarely eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of space to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry is usually neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 1.5 or 2cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 80 liters, bigger ones are better for sure. Dense vegetation combined with many roots and wood and free space areas for the males to impose and fight make sense. The current should be moderate, especially as the oxygene level should be quite high (at least 8mg/l) for this spring inhabiting species.

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. The related Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis was observed at la Mintzita spring looking for small sources of food between rocks and picking up small Copepods or organic matter. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is anything else but shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or gets too warm (25°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.