Goodea atripinnis (including gracilis and luitpoldii)

JORDAN, D. S. (1880): Notes on a collection of fishes obtained in the streams of Guanajuato and in Chapala Lake, Mexico, by Prof. A. Duges. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 2, for 1879: pp 298-301

Collection-number: United States National Museum, Cat. No. USNM-23137.

David S. Jordan did neither deposit a Holotype nor did he commit a collection date to paper. The species is described from numerous specimens, he received from Alberto Dugès, who collected them at several locations in Guanajuato. The four largest ones (of about 10mm total length) Dugès obtained from the area of León, another locality is given with a salty lake on a volcanic plain near Valle de Santiago. Typical for this species should be tricuspid teeth in a single row, which was a mistake and led to confusion in the decades after (see therefore the chapter "Remarks"). Concerning information about the Holotypes of other, now with atripinnis synonymized species, except for figures, go also to this chaper.

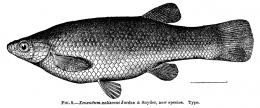

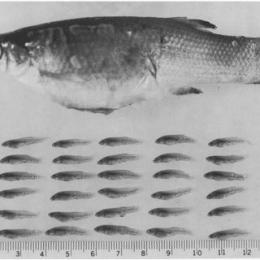

The left picture in the first row shows a drawing of one of the types of Goodea atripinnis, the middle one a painting of one of the types of Characodon luitpoldii and the right one a drawing of the Holotype of Xenendum caliente. The two pictures in the second row show a drawing of the Holotype Xenendum xaliscone (left) and a photo of the Holotype of Goodea gracilis (right):

The types were partly collected near the town of León in the state of Guanajuato, but also at other locations. Tarleton Bean (1880) mentioned specimens of Goodea sp. having been collected by Dugès in a salt lake in the middle of a little volcanic plain in Valle de Santiago, Guanajuato. These were also mentioned together with those from León by Jordan and Evermann in 1896.

The species name is derived from the Latin with the adjective "ater", black and "pinna", the fin. The epithet means therefore "(with) black fins". His preserved specimens showed black unpaired fins and this character attracted Jordans attention.

David Jordan erected the genus 1880 in honour of George Brown Goode, who ran at this time both the fish research program of the U.S. Fish Commission and the Smithsonian Institution (from 1873 to 1887). This genus, simply "Goodes one" in translation, made his name immortal by finally naming the subfamily Goodeinae and even the whole family Goodeidae.

Goodea sp. Bean, 1880

Characodon atripinnis Bean, 1888

Characodon variatus Woolman, 1894 (misidentification)

Characodon luitpoldii von Bayern and Steindachner, 1894

Xenendum caliente Jordan & Snyder, 1900

Xenendum xaliscone Jordan & Snyder, 1900

Xenendum luitpoldii Jordan & Evermann, 1900

Goodea caliente Meek, 1902

Goodea luitpoldi Meek, 1902

Goodea calientis Regan, 1907

Goodea gracilis Turner, 1937 (nomen nudum)

Goodea gracilis Hubbs & Turner, 1939

Goodea atripinnis calientis de Buen, 1947

Goodea atripinnis atripinnis de Buen, 1947

Goodea atripinnis martini de Buen, 1947

Goodea atripinnis luitpoldii de Buen, 1947

Goodea atripinnis subsp. de Buen, 1947

Goodea atripinnis xaliscone de Buen, 1947

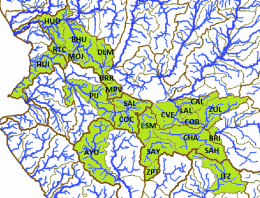

The Blackfin Goodea is native to nine Mexican federal states and introduced to two more (Durango and the Distrito Federal). The distribution range is the largest of all Goodeid species extending from Hidalgo in the E to Nayarit in the W spanning a distance of about 600km beeline and from Michoacán in the S to Zacatecas in the N, over approximately 350km beeline. It was historically known from the lower sections of the Upper (about Maravatio) and from the Middle Río Lerma basin, there including all affluents, especially the bigger rivers: ríos Laja, Guanajuato and Turbio, from the Río Angulo drainage including the Lago Zacapú, from the Lower Río Lerma drainage including the Río Duero and other smaller affluents, from the ríos Verde (Jalisco, not San Luis Potosí), Juchipila and Bolaños (Río Grande de Santiago affluents) drainages, and from the Upper Río Grande de Santiago/ Laguna Chapala drainage. Furthermore it is known from the Upper Río Ameca drainage, the endorheic lagunas San Marcos, de Sayula, de Zapotlán, Zacoalcos and Atotonilco, from headwaters of the Río Ayuquila, Río Armería drainage (most likely introduced) and from headwaters of the ríos Santa María and Moctezuma, Río Pánuco drainage, including the endorheic Río Venados (Río Metztitlán) drainage in Hidalgo. Additionally the species occurs in the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia (including the Lago Cuitzeo), Laguna Yuriría, Lago de Pátzcuaro and lagunas de Zirahuén and Magdalena basins. It even reaches the ríos Grande and Turundeo headwaters in the Río Balsas drainage and is one of very few Goodeid species reaching the ríos Huicicila and Mololoa drainages in Nayarit, the last one being an affluent of the Río Grande de Santiago just before it reaches the Pacific. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered. All in all, 25 subpopulations are distinguished:

1. Upper Río Lerma subpopulation (including the Río Cachiví near Maravatio de Ocampo)

2. Middle Río Lerma subpopulation (type subpopulation; including the ríos Laja, Guanajuato, Turbio)

3. Laguna Yuriría subpopulation

4. Río Angulo subpopulation (including the Lago Zacapú)

5. Lower Río Lerma subpopulation (including the Río Duero)

6. Upper Río Grande de Santiago/Laguna Chapala subpopulation

7. Río Verde subpopulation

8. Río Juchipila subpopulation

9. Río Bolaños subpopulation

10. Río Mololoa subpopulation (in Tepic, lower Río Grande de Santiago affluent)

11. Río Huicicila subpopulation (including the Arroyo Compostela)

12. Laguna Magdalena subpopulation

13. Upper Río Ameca subpopulation (including the Río Teuchitlán)

14. Upper Río Ayuquila subpopulation (Río Armería drainage, most likely introduced)

15. Lagunas Atotonilco/San Marcos subpopulation

16. Laguna de Sayula subpopulation

17. Laguna de Zapotlán subpopulation

18. Río Santa María subpopulation

19. Río Moctezuma subpopulation

20. Río Venados (Río Metztitlán) subpopulation

21. Río Grande subpopulation (Cotija)

22. Río Turundeo subpopulation (around Ciudad Hidalgo)

23. Río Gande de Morelia subpopulation (including the Lago Cutzeo and the Presa Cointzio)

24. Lago de Pátzcuaro subpopulation

25. Laguna de Zirahuén subpopulation

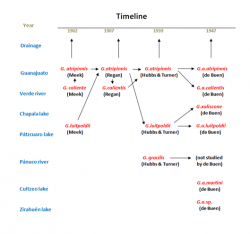

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

Goodea atripinnis is a nightmare for taxonomists. There are so many different types of Goodea, that actually only two ESU's are distinguished, though the number of forms are many. Gooat1 is in use for all the fish west of the Río Pánuco system and Gooat2 for the ones from the Río Pánuco system, that are by some scientists still named Goodea gracilis.

The left map in the upper row shows the ríos Tepalcatepec (TE), Cutzamala (CU) and the Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo (TI) basins of the Hydrographic Region Balsas, the Lago de Chapala (CH), Río Santiago-Guadalajara (SG), Río Santiago-Aguamilpa (SA), Rio Lerma-Chapala (LC), Río Lerma-Salamanca (LS), Río Lerma-Toluca (LT), Río Laja (LA), Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC), ríos Juchipila (JU), Verde Grande (VG) and Bolaños (BO) basins of the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, the Río Ameca-Atenguillo (AA) and Presa La Vega-Cocula (VC) basin, Hydrographic Region Ameca, the ríos Tamuín (RT) and Moctezuma (MO) of the Hydrographic Region Pánuco and the Río Huicicila-San Blas (HU) basin of the Hydrographic Region Huicicila on a Mexico map. The occurence in the Río Armería basin (AR) from the Hydrographic Region Armería-Coahuayana is probably not autochthonous. The middle map in the upper row shows more or less northern subbasins, precisely spoken from the ríos Juchipila, Verde Grande and Bolaños basins, and northern subbasins of the Río Santiago-Guadalajara basin. It is not totally clear if all of these subbasins are populated with this species, but very likely. However, due to the huge number of subbasins, we just tell them for the corresponding basins. Río Bolaños basin: Ríos Bolaños Alto (BOA) and Bajo (BOB), Carbonera (CRB), Valparaíso (VLP), San Mateo (RSM), Tlaltenango (RTL), Colotlán (COL), Chico (CHO), Tepetongo (RTP) and Jeréz (JER) subbasins. Río Juchipila basin: Ríos Juchipila-Moyahua (RJM), Juchipila-Jalpa (JUJ), Juchipila-Malpaso (JUM), Mezquital (MEZ), Calvillo (CAV), Zapoqui (ZAP) and Palomas (PAL) subbasins. Río Verde Grande basin: Ríos Verde Grande (RVG), Los Lagos (RLL), Tepatitlán (TPT), del Valle (VAL), San Miguel (SMI), Teocaltiche (TEO), Grande (GRA), Encarnación (ENC), Aguascalientes (AGU), Morcinique (MOR), San Pedro (RSP) and Chicalote (CHI) subbasins. Río Santiago-Guadalajara basin: Ríos Verde-Presa Santa Rosa (VSR), Gigantes (GIG), Cuixtla (CXT), Chico (RCH) and Presa Santa Rosa-Río Bolaños (SRB) subbasins. The right map in the upper row shows eastern subbasins, all of them belonging to the ríos Tamuín and Moctezuma basins from the Hyrographic Region Pánuco. Again, it is not clear if all these subbasins are populated, even more, if there are not more subbasins with autochthonous populations of this species. However, we try to be as accurate as possible. Besides the ríos Santa María Alto (RSA) and Bajo (RSB) from the Río Tamuín basin, there are the ríos San Juán (RSA), Moctezuma (MOC), Extoraz (REX), Amajac (AMA), Metztitlán (MTZ), Alfajayucan (ALF), Tula (TUL), Tecozutla (TEC), Arroyo Zarco (RAZ), Actopan (ACT) and Prieto (PRI), and the Drenaje Caracol (DCA) subbasins, all from the Río Moctezuma basin. The left map in the lower row shows southern and central subbasins, mainly from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, supplemented with the Lago de Zirahuén (ZIR) subbasin, Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo basin, and the Río Tuxpan subbasin (TXP), Río Cutzamala basin, both from the Hydrographic Region Balsas. Back to the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, the species doesn't seem to be broader distributed within the Río Lerma-Toluca basin, eventually only in the ríos Tigre (TIG) and Solís (SOL) and the Arroyo Tarandacuao (TAR) subbasins. However, it is distributed in the whole ríos Laja, Lerma-Salamanca, Lerma-Chapala and Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basins. Again, due to the huge number of subbasins, we just tell them for the corresponding basins. Río Laja basin: Ríos Laja-Celaya (LAC), Laja-Peñuelitas (LPE), Apaseo (RAP) and the Presa Ignacio Allende (PIA) subbasins. Río Lerma-Salamanca basin: Ríos Salamanca-Río Angulo (SAN), Solís-Salamanca (SOS), Temascatio (TEM), Guanajuato (GUA), Turbio-Corralejo (TCO), Turbio-Manuel Doblado (TMD) and Trubio-Presa Palote (TPP) subbasins. Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basin: Lagos de Cuitzeo (CUI), de Pátzcuaro (PAT) and de Yuriria (YUR) subbasins. Rio Lerma-Chapala basin: Ríos Duero (DUE), Angulo (ANG), Angulo-Río Briseñas (ABR), and Arroyo Huascato (HUA) subbasins. Also to this basin belongs the Río Briseñas-Laguna Chapala (BRI) subbasin shown on the next map. This map, the right one in the lower row, shows western and southwestern subbasins. There are in the south from the Río Tepalcatepec basin the Río Itzícuaro subbasin (ITZ) and from the Río Armería basin the Río Ayuquila subbasin (AYU), the last one with some uncertainties concerning autochthony. Goodea atripinnis occurs additionally in the whole Lago de Chapala basin with the lagunas Chapala (CHA), de San Marcos (LSM), de Sayula (SAY), de Zapotlán (ZAP) and the Río Sahuayo (SAH) subbasins and the southern subbasins from the Río Santiago-Guadalajara basin (the northern ones are shown on the middle map of the upper row). These are the ríos Corona-Río Verde (CVE), La Laja (LAL), Calderón (CAL), Zula (ZUL) and the Laguna Chapala-Río Corona (COR) subbasins. It is also known from the Hydrographic Region Ameca from the Río Ameca-Pijinto (PIJ) subbasin, Río Ameca-Atenguillo basin, the ríos Salado (SAL) and Cocula (COC) subbasins, Presa La Vega-Cocula basin, and the Río Huicicila (HUI) subbasin, Río Huicicila-San Blas basin, Hydrographic Region Huicicila. The Río Santiago-Aguamilpa basin is the last one with autochthonous populations of the Blackfin Goodea. Here it occurs in the ríos Huaynamota-Océano (HUO), Tepic (RTC), Bolaños-Río Huaynamota (BHU), Mojarras (MOJ), de la Manga (DLM), Barranquitas (BRR) and the Laguna Magdalena-Laguna Palo Verde (MPV) subbasins:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Least Concern

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Least Concern/declining: „This species has the largest distribution of any goodeid species. Its native range includes the Lerma, upper Santiago (including Lake Chapala), upper Ameca, upper Armería, and upper Balsas river basins on the Pacific slope, the endorheic Lake Zirahuén, Lake Pátzcuaro, and Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basins in central Mexico, and the upper Pánuco River basin on the Atlantic slope. Many years ago, Goodea was introduced and became established in the Valley of Mexico. Also, an introduced population was recently discovered in the upper Mezquital River basin within the range of Characodon near Durango (Michael Tobler, Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas, USA, unpublished data). Some early authors (e.g., Meek, 1904; Mendoza, 1962) considered the Lake Pátzcuaro population to be a different species, G. luitpoldi, but recent genetic and morphological analyses indicate that this population is not distinct from G. atripinnis (Doadrio and Domínguez-Domínguez, 2004; Webb et al., 2004; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2010). Other authors have considered the Pánuco River basin population a distinct species, G. gracilis (e.g., Doadrio and Domínguez-Domínguez, 2004; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005). Although there are minor genetic and morphological differences between Pánuco River basin populations and other Goodea populations, the Pánuco population is more appropriately considered as a separate ESU rather than a separate species (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2010). Goodea atripinnis remains common in many areas and is probably still the most abundant goodeid species overall, but the distribution and abundance of both ESUs have steadily declined during the last 25 years (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1999; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005b; Mercado-Silva et al., 2006). Despite decreases in distribution and abundance, Gooat1 still qualifies as least concern and remains common in many areas. It appears to be relatively tolerant of poor water quality compared to other goodeids (Rueda-Jasso et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the trends for this ESU are not encouraging. Historically, this ESU supported commercial fisheries in the larger lakes where it occurred, but in recent years it has been eliminated from Lake Zirahuén, reduced to a small remnant population in Lake Pátzcuaro, and greatly decreased in number in Lake Chapala and Lake Cuitzeo, largely owing to predation by and competition with non-native fish species. It is still harvested and eaten in Lake Pátzcuaro and Lake Zacapu, Michoacán. Pollution and habitat modifications have devastated populations in many areas of the Lerma and upper Santiago basins. Gooat2 is endangered, and only four or five small populations persist in the upper Pánuco River basin. Decreases there have been caused primarily by water diversions and groundwater pumping, which have eliminated habitat.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: no categoría de riesgo (no category of risk)

The habitats are very versatile, including lakes, ponds, streams, springs and outflows. The species goes down to 1.7m, but prefers usually depths of less than 0.5m. The water may be clear, turbid or muddy and currents are none to sometimes moderatly strong. Different substrates like mud, clay, sand, gravel and rocks occur. The vegetation is rarely sparse, typical are green algae plus Chara, water hyacinths, Potamogeton, Lemna and Nasturtium. This species is almost ubiquitous in its distribution range and occurs even in habitats, where no other Goodeid species is able to survive. Goodea atripinnis is a Goodeid success story!

Underwater-Videos:

Following Miller, young occur from the end of January to the middle of July, indicating a long reproductive period. On the other hand, Mendoza (1962) found young in the Pátzcuaro lake from June to August, indicating just one brood per year for at least this lake. The capture of young indicates, that the reproduction in the Río Panuco basin is from midwinter to late spring (early February to May or June) and may extend throughout autumn (17mm young taken on November, 23rd). Goodea atripinnis is a prolific fish; a very large female (149mm SL) contained 167(!) embryos ready for birth. These fish generally swim from midwater to bottom, feeding during the day on aufwuchs. It also forms aggregates of stationary fish just off the bottom (Kingston, 1979).

The left picture shows a female of Goodea atripinnis with opened ovary to show the fry inside, the right one an opened female and the removed fry:

The gut is elongated (about 230% of the standard length) and convoluted, and the mouth is dorsally oriented. The marginal teeth of premaxillary and dentary are arranged in two rows of bicuspid teeth, followed by a set of small unicuspid teeth. This species is definitely herbivorous, feeding mainly on filamentous green algae and soft water plants, additionally detritus, small Crustaceans and Molluscs. Jordan in his orginial paper described the intestinal canal as "considerably convoluted and filled with mud."

Jordan described the colour of the fish in spirit as "bluish above, sides nearly plain, with a silvery streak along each series of scales. Vertical fins obscurely marked, each of them chiefly black, especially on the distal half." In life, Goodea atripinnis can be differing a lot in colour. Some specimens get uniform light grey when adult or nearly black, others can be greenish with yellow to orange belly. Silvery bodies with yellow fins are common.These can turn into black or grey. Broad lateral bands composed of small dots or blotches are not rare. Some populations are greyish brown, some spotted like a Leopard. So similar this species is in general shape, so different it can be in colouration.

Hieronimus (1995) distinguishes between three different basal types of colouration: the first type is totally silvery in both sexes without any black fins, the second type greenish-yellow with males with green flanks. The belly may be yellow and females display black unpaired fins when being at ease, whereas the males show yellow fins. The third type displays a strong, dark, lateral band in both sexes with also black unpaired fins in the female gender when feeling comfortable. Following him, all three types may be found at one location with different intermediate stages. Observations in the aquarium give the impression, that even within one specimen these types can change at different conditions.

Males and females of the Blackfin Goodea are not easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Goodea atripinnis have a slightly bigger Dorsal fin than females. A difference in colouration is usually not visible.

Due to the large area this species is inhabiting and the many different populations, the relationship of this species led to some confusion, and it still does. This is an attempt to bring some light into the darkness of the Goodea - taxonomy.

The early years: From Characodon and Xenendum to only Goodea (left picture below)

In 1887, seven years after the description by Jordan, Tarleton H. Bean got the opportunity to examin the types of Goodea atripinnis. In contrary to Jordan, he found villiform teeth behind the incisors and therefore transfered the species into the genus Characodon. Six years later (1894) Franz Steindachner forwarded a letter from Princess Therese of Bavaria to privy councillor Franz Ritter von Hauer, who had the chairmanship of the meeting of the mathematic-scientific class in Vienna in June 1894, where she described more or less with the help of Steindachner (probably he did the description in reality alone) from two females of 13 and 13.6mm, that she obtained from fishermen from the Pátzcuaro lake, a new species of fish. The species was named Characodon luitpoldii in honour of her father, Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria. Two years later (1900) Jordan and John Otterbein Snyder described two species in their newly erected genus, Xenendum, with bicuspid teeth instead of tricuspid like in Goodea, namely Xenendum caliente and xaliscone. The first species was described after a male that Snyder collected on January the 9th, 1899, in the Río Verde near the town of Aguascalientes (Cat.No. LSJrUM-6147). The Holotype of the second species was a female, collected also by Snyder on December the 26th, 1898, in the Chapala lake near Ocotlán (Cat. No. LSJrUM-6148). Despite of the resemblance, Jordan consequently sticked to Goodea atripinnis and the Xenendum species belonging to two different genera, as he still believed in the tricuspid teeth he thought he had seen in the collection from Guanajuato. In the same year, he and Barton Evermann, transfered Characodon luitpoldii into the genus Xenendum because of its biscupsid teeth. Already in 1902, so just two years later, Seth Eugene Meek asked T. H. Bean to check Jordans types again and Bean discovered the mistake with tricuspid teeth in Jordans type material of Goodea atripinnis. Meeks reaction was to confirm this species, to transfer luitpoldii into Goodea and synonymize Xenendum xaliscone with it. Furthermore he accepted at the beginning Xenendum caliente as Goodea caliente, but synonymized this species with atripinnis already in the same year, reducing the number of species in Goodea to two, atripinnis and luitpoldii. Only five years later (1907), Charles Tate Regan synonymized luipoldii with atripinnis, but erected Goodea calientis again, this time the epithet adapted in the correct way.

The next step: Hubbs & Turner versus Fernando de Buen (right picture below)

Despite of Hubbs' description of Goodea captiva (1924) after some specimens from Jesus Maria, Río Pánuco drainage, that was transfered into the new genus Xenoophorus by Hubbs and Turner (in Turner, 1937), he described again with Turner in 1939 a "true" Goodea from the Pánuco drainage: Goodea gracilis. The Holotype is an adult female of 39mm standard length collected by Gordon, Whetzel and Ross on March the 21st, 1932, in the Río Santa Maria at Santa Maria del Río in San Luis Potosí (Cat. No. UMMZ-108552). Together with this female were taken three male Paratypes of 34 to 43mm. Fernando de Buen y Lozano was not satisfied with lumping all these different forms of Goodea. On the other hand, he found the differences not strong enough to justify species rank. His solution was to accept the four forms Jordan treated as valid (Goodea atripinnis, Xenendum caliente, luipoldii and xaliscone) as subspecies of Goodea atripinnis. Furthermore he described after three female fish of 85 to 93mm that his son collected in the Río Grande de Morelia, probably in summer 1941, a fifth subspecies: Goodea atripinnis martini. A single specimen in bad condition, that Mario del Torre collected in the Zirahuén lake in August 1934, made him think of a sixth subspecies, but the material was too poor. As Goodea gracilis was not within his area of investigation, he didn't have a bearing on this species. So with the 1950's, depending on the scientists doctrine, either three species were accepted (atripinnis, gracilis and luitpoldii) or two (atripinnis, gracilis) with several subspecies.

The recent years: The new population of Hidalgo and the end of Goodea gracilis

Morphometric and phylogenetic results by the end of the 1990`s and beginning Millenium made clear, that Goodea luitpoldii couldn't be held any longer as distinct species, and there was also no possibility to distinguish any subspecies. Too many transitions between the many different forms made it almost impossible to set limits to species. Finally, as nobody went into detail with Goodea gracilis, two species (atripinnis, gracilis) without subspecies were widely accepted. In 2010 then, few specimens of the genus Goodea were found in the endorheic Río Metztitlán valley, federal state of Hidalgo. Comparing measures from these few individuals show intermediate results between the two accepted species gracilis and atripinnis, so the final position of this population wasn't sure at all. However, following distribution patterns, it should rather belong to Goodea gracilis. Phylogenetic results in 2012 revealed, that Goodea gracilis is phylogenetically nested within atripinnis, so there is no possibility to separate these two species. The last results so far (Beltrán-Lopez et al., 2021) found two clusters within Goodea. One is summarizing all the populations from the Middle Río Lerma basin and its affluents, the Lago de Cuitzeo drainage, the Pánuco river populations and populations of the Río Grande de Santiago affluents (Río Verde, Juchipila aso.). Due to its distribution in the more northeastern part of the distribution range, it is called "Northeastern clade" by the authors. The second cluser encompasses all populations of the Lower Río Lerma and Chapala lake as well as the populations from the ríos Ameca and Ayuquila and adjacent endorheic basins (Magdalena lake and the San Marcos, Sayula and Zapotlán lagoons.). The authors called it "Southwestern Clade". However, the differences between these clades are not very big, so a splitting into two species doesn't make sense according to these results. At least until more comprehensive phylogenetic methods will be applied, it is best to summarize all Goodea forms within the single species Goodea atripinnis, and it is very likely, that it has to be accepted finally that Goodea is a polymorphic, but monospecific genus.

The genus Xenendum is one of only five that have been erected exclusively for Goodeid fish and lateron became synonyms. In case of Xenendum it goes back to a mistake made by D. S. Jordan in 1880, when he erected the genus Goodea for fish with what he thought were tricuspid teeth, and 20 years later together with Snyder this genus for fish with biscuspid ones. When the original Jordan material of Goodea was studied again by T. H. Bean on behalf of Meek in 1902, and it was discovered, that the types of Goodea had only biscuspid teeth not trisuspid ones, the genus Xenendum correctly became a synonyme of Goodea. The etymology of the generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek with ξένος (xénos) meaning strange and ἔνδον (éndon) inner or internal. Herewith Xenendum can be translated with "internally strange", for sure an indication for the - at the beginning of the 20th century still unusual - presence of an ovarium filled with young fish ready to be born.

Looking on the biotopes of Goodea atripinnis, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with none to moderate or slightly swift current, structured with rocks, roots and small areas with dense submerse vegetation. Intraspecific aggession can be rarely observed, the level of aggression between the fish is almost zero. Fry is usually not eaten, so it is easy to get fast a big and flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is depending on the end size of the population and should therefore be between at least 100 up to 250 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. A bit with roots and/or rocks structured tanks with few patches of dense submerse vegetation in the corners and bigger free areas to swim seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate.

In the wild, adults of this species feed mainly from algae and aufwuchs, so much light to help algae grow and feeding with vegetables and additionally fiber-rich middle sized food from animalistic sources will be best for this fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally freeze dried food like Brine Shrimps is eaten greedy. The species is anything else but shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids. Therefore an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 25°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, and for regulating the number of fry, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species does very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15 or 17°C (depending on the origin of the population) and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15 or 17°C (depending on the origin of the population) by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Gooat1-ACA-Mar

Population: Maravatio (aka San Miguel)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Toluca

Subbasin: Arroyo Cavichi

Locality: Manantial (spring) San Miguel in Maravatio

2. Gooat1-COR-Sant

Population: Río Santiago

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Santiago-Guadalajara

Subbasin: Laguna Chapala-Río Corona

Locality: Río Santiago, below the dam about 2.5km E of Atotonilquillo

3. Gooat1-SAL-RTeu

Population: Río Teuchitlán (aka Balneario del Rincón, Teuchitlán)

Hydrographic region: Ameca

Basin: Presa La Vega-Cocula

Subbasin: Río Salado

Locality: Río Teuchitlán -spring "El Rincón"

4. Gooat1-LPE-Xoc

Population: Xoconoxtle

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Laja

Subbasin: Río Laja-Peñuelitas

Locality: Río San Juán, at bridge E of Xoconoxtle El Grande

5. Gooat1-GUA-RSil

Population: Río Silao

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Salamanca

Subbasin: Río Guanajuato

Locality: Río Silao

6. Gooat1-ZIR-Opo

Population: Opopeo (aka Lago de Opopeo, Laguna de Opopeo)

Hydrographic region: Balsas

Basin: Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo

Subbasin: Lago de Zirahuén

Locality: Estanque de Condembas and its effluent in Opopeo

7. Gooat2-SMA-JMar

Population: Jesús María (aka Goodea gracilis)

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Santa María Alto

Locality: Jesús María dam, about 19km S of San Luis Potosí

8. Gooat2-RSA-SJRio

Population: San Juán del Río (aka Goodea gracilis)

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Moctezuma

Subbasin: Río San Juán

Locality: Río San Juán, at San Juan de Río

9. Gooat2-PSP-OJal

Population: Ojuelos de Jalisco

Hydrographic region: El Salado

Basin: San Pablo y otras

Subbasin: Presa San Pablo

Locality: artificial lagoon next to the road, about 6km NE of Ojuelos de Jalisco