Xenotoca variata

BEAN, T. H. (1887): Descriptions of five new Species of Fishes sent by Prof. A. Dugès from the Province of Guanajuato, Mexico. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 10: pp 370-375

Collection-number: United States National Museum, Cat. No. USNM-37809.

The types are four females, collected by Alfredo Dugès before 1887 (precise collection date unknown, but there is the date of another collection of this species noted with September the 1st, 1886). In the same paper, T. H. Bean described Characodon ferrugineus after a pair (Cat. No. USNM-37810). This species, he synonymized five year later with variatus. Go to the chapter "Remarks" for more details about the types.

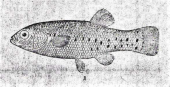

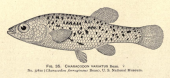

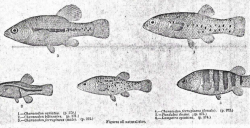

The left picture shows a drawing of one of the types of Xenotoca variata, the middle one a drawing of the male type of Characodon ferrugineus (from Meek, 1904), and the right one a drawing from the female type:

The types were collected by Alfredo Dugès, probably in streams of the "Province of Guanajuato". This is likely as Dugès collected primarily in this federal state.

The species epithet "variata" is derived from the Latin word "variare" means "to vary". The adjective has the meaning "varying". Bean didn't explain, why he had chosen that name, but probably because his attention was attracted by the colouration, as he found "on the sides several - differing in shape, size and number - dark blotches".

The genus Xenotoca was erected for Characodon variatus by Hubbs and Turner in Turner, 1937, because "this species differs from Characodon (lateralis) in numerous internal as well as external features. Characters distinguishing Xenotoca from Characodon involve the ovarian anatomy, the form and structure of the trophotaeniae, and some superficial features". The generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek with the word ξένος (xénos) meaning strange and and τόκος (tókos) offspring. Xenotoca can therefore be translated with "a strange type of offspring".

Characodon variatus Bean, 1887

Characodon ferrugineus Bean, 1887

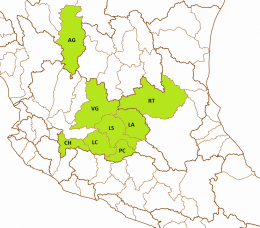

The Jeweled Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal states of San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Michoacán, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Guanajuato and Zacatecas. It historically occured in the Middle Río Lerma drainage including all affluents like the bigger rivers (ríos Laja, Guanajuato and Turbio), in the Laguna Yuriría, in the Río Angulo drainage (including the Lago Zacapú) and in headwaters of the ríos Santa María (Río Panuco drainage) and Verde (affluent of the lower Río Lerma). Vouchers indicate that this species also populated the lower Rio Lerma basin including the Río Duero and the Río Grande de Santiago/ Laguna Chapala basin (where it still can be found in the Lagos Los Negritos ponds), but it seems to be completely extirpated from these areas except for the Lagos Los Negritos. It is additionally known from springs within the ríos El Muerto and Frío drainages, affluents of the endorheic Río Aguanaval in Zacatecas. Affiliated to different drainages, eight subpopulations can be distinguished: The Río Aguanaval subpopulation, the Lagos Los Negritos subpopulation, the Lower Río Lerma subpopulation (probably Extinct), the Río Angulo subpopulation, the Río Verde subpopulation, the Middle Río Lerma subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Laguna Yuriría subpopulation and the Río Pánuco subpopulation. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Xenotoca variata we actually are able to distinguish four different ESU's. To Xenva1 belong all populations from the Río Santa Maria drainage and populations along the middle and upper Río Lerma downstreams to the Río Grande de Santiago basin (Río Verde). Xenva2 is restricted to the Los Negritos ponds east of the Chapala lake, whereas Xenva3 is used for the specimens of the Lago de Zacapu and its drainage. Xenva4 encompasses fish from the Aguanaval drainage, a system in the state of Zacatecas and now isolated from the Río Grande de Santiago system but flowing northwards into the endorheic Bolsón de Mapimi area. Xenva5 is still in use for the not yet described species from the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia /Lago de Cuitzeo basin.

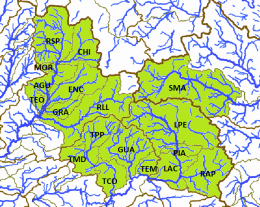

The left map of the upper row shows the Río Tamuín (RT) basin from the Hydrographic Region Pánuco, the Río Laja (LA), the Río Lerma-Salamanca (LS), the Río Lerma-Chapala (LC), the Lago de Chapala (CH), the Río Verde Grande (VG), the Lago Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC) basins from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, and the Río Aguanaval (AG) basin from the Hydrographic Region Nazas-Aguanaval. All of them proved by vouchers to be part of the distribution area of the Jeweled Splitfin. However, the distribution pattern makes it likely that this species once occured also in the Fresnillo-Yesca basin from the Hydrographic Region El Salado, but as the distribution pattern of this species is not fully understood, it is not considered on this map here. The right map of the upper row shows the confirmed subbasins of the Río Aguanaval basin, the ríos de Santiago (RDS) and Saín Alto (SAA) subbasins. Probably the species occurs or occured in adjacent subbasins as well, but as it is not fully clear, with which system the Río Aguanaval was connected before it was captured from the Río Lerma system (though it seems very likely that it was the Río Verde), none of them is considered on this map here. The left map of the lower row shows the subbasins from the northern half of the distribution area including the Río Santa María Alto subbasin (SMA) from the Río Tamuín basin, and the Río Laja subbasins, namely the ríos Laja-Celaya (LAC), Laja-Peñuelitas (LPE), Apaseo (RAP) and the Presa Ignacio Allende (PIA) subbasin. The map also includes the ríos Temascatio (TEM), Guanajuato (GUA), Turbio-Corralejo (TCO), Turbio-Manuel Doblado (TMD) and Turbio-Presa Palote (TPP) subbasins from the Río Lerma-Salamanca basin, and several subbasins from the Río Verde Grande basin. Those are the ríos Los Lagos (RLL), Encarnación (ENC), Grande (GRA), Teocaltiche (TEO), Aguascalientes (AGU), Chicalote (CHI), Morcinique (MOR), and San Pedro (RSP). The rightr map in the lower row shows the subbasins from the southern half of the distribution area of the Jeweled Splitfin. Still populated are the ríos Salamanca-Río Angulo (SAN) and Solís-Salamanca (SOL) subbasins from the Río Lerma-Salamanca basin, the Lago de Yuriria subbasin (YUR) from the Lago Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basin, the Río Angulo subbasin (ANG) from the Río Lerma-Chapala basin, and the Los Negritos ponds from the Río Sahuayo subbasin (SAH), Lago de Chapala basin. Vouchers prove, that the species occured in historical times at least in the ríos Duero (DUE) and Angulo-Río Briseñas (ABR) subbasins from the Río Lerma-Chapala basin, and from the Laguna Chapala (CHA) subbasin directly. It seems very likely that the species additionally occured in the Río Briseñas-Laguna Chapala (BRI) and the Arroyo Huascato (HUA) subbasins from the Río Lerma-Chapala basin:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Least Concern

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Least Concern/declining (including Xenotoca cf. variata): „This species is broadly distributed in central Mexico throughout the Lerma and upper Santiago river basins on the Pacific slope, the endorheic Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basin in central Mexico, and a small area of the upper Pánuco River basin on the Atlantic slope (Miller et al., 2005). It reaches a relatively large total length (~100 mm) and is caught and eaten in Zacapu Lake, Michoacán. It is highly tolerant of pollution and habitat modifications and, along with Goodea atripinnis, still persists in areas where other goodeid species have been eliminated. Xenotoca variata is currently found at many locations throughout its historic range. Nonetheless, the species has declined in recent years, disappearing from heavily polluted areas of the Santiago and Lerma basins and from reservoir and lake habitats where the non-native Micropterus salmoides (Centrarchidae) has become established (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1998, 1999; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005; Mercado-Silva et al., 2006). We recognize five ESUs based on genetic analyses (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2010). Xenva1 is classified as least concern and broadly distributed in the Santiago, Lerma, and Pánuco basins. Many populations are still present, but others have disappeared from the Lerma River and its major tributaries due to water pollution. Xenva2 is vulnerable and known from a single location, Lake Los Negritos (also known as La Alberca). The population there remains moderately large but appears to have declined because of non-native species. Xenva3 is vulnerable and found in the Angulo River drainage in the middle Lerma River basin. It has declined in abundance in the river but remains relatively common in the headwaters at Lake Zacapu. Xenva4 is vulnerable and known from the endorheic Aquanaval River basin. It has declined because of overuse of water and habitat loss. Xenva5 is least concern and found in Lake Cuitzeo and the Grande de Morelia River basin. It has declined in the lake proper owing to habitat loss and poor water quality and has been eliminated from the Grande de Morelia River near the city of Morelia, but still remains common at several locations. This last ESU is particularly distinctive genetically and may eventually be described as a separate species.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: no categoría de riesgo (no category of risk)

Xenotoca variata prefers habitats like clear to murky rivers and lakes with currents of moderate to absent. It can be detected in shallow water (less than 1m deep) over substrates from deep mud to rocks. Usually, vegetation is abundant. Detected genera have been (besides much floating or attached green algae) Potamogeton, Eichhornia, Nasturtium and Myriophyllum. The Jeweled Splitfin was seen on several surveys of the GWG to the ríos Turbio, Guanajuato, Angulo and Laja in 2017. It occured mainly in shallow creeks, where it was hiding between rocks and filamentous algae. In Tarejero, fish were fed with Tortillas by people and therefore occured in masses, but most of the habitats were populated in medium numbers. It was seen on surveys to Jesus Maria in 2014 and 2015 in a shallow pebbly pool and 2016 in the pond at Los Negritos, also in medium numbers. In 2015, it was rediscovered in Atotonilco, Aguanaval river drainage, where the species lives in a shallow outflow creek of a thermal spring. It occurs there mainly in manmade ditches and pools.

Underwater-Videos:

Captures of young or pregnant females indicate that the reproduction occurs from at least February through May. On surveys of the GWG to rivers of Guanajuato and the Río Angulo drainage in March 2017, the group was able to find pregnant females and young fish with 2 and 2.5cm, so they were from the same year, born in January or February.

The dentition suggests omnivorous feeding habits with the length of the gut differing between 1 and 1.5 times the size of the body. Due to the large distribution area and the many different populations and populated habitats, different food preferences, eventually even quite flexibel depending on the nutrition available, seem to be likely. In many river habitats of Guanajuato, the Jeweled Splitfin cooccurs with the herbivorous Goodea atripinnis, so probably Xenotoca variata has mainly omnivorious feeding habits with a tendency to carnivorous ones, which is also supported by the length of the gut of maximal 1.5 times the TL.

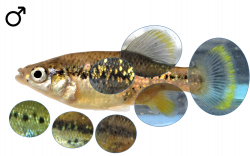

There is no typical Xenotoca variata colouration, but there are some characters that usually appear. So have females in most of the cases a midline formed by a differing number of blotches. Those can be few and distinctively and regularly set like in the Los Negritos population, or the blotches can coalesce into a line like in many others. In some populations, there is no midline present and the females show only few black blotches on the belly and sides. A good number of populations have the belly heavily blotched, a few more even the back, but there is no colour pattern like in the Polkadot Splifin with many fine dots on the belly and unicoloured back. Usually females are grey, greyish-whitish, or whitish-silvery coloured, but the populations from the Aguanaval show a tendency to silvery-blue, some others can appear yellow or yellowish. The fins are clear (the similar looking Butterfly Splitfin females have black lines in their Caudal fins) and some females have the belly coloured partly bright yellow. The only other colour accents appearing are very few and small shiny scales on the flankes in some fish. Males differ much more in colouration. While the ones from the population from Los Negritos look almost like females with only the caudal fin having a fading yellow terminal band, most of the others are extremely colourful. Males from the Aguanaval drainage have a dark midline and the sides blue or bluish-silvery with small but many shiny scales on the flankes. The Caudal fins show a broad orange or dark yellow terminal band, sometimes even the Anal and Dorsal fins are orange or yellow. The males from the other populations from the ríos Lerma, Verde, Angulo and Pánuco drainages have their ground colour varying from grey over brownish to yellow or greenish, the belly is mostly contrasting to the back in white, whitish, yellowish or bright yellow. The Caudal fin has got always a terminal band in yellow, creme or white, in some populations followed by a broad black or grey field (in contrast to Ameca splendens, where a distinct black line borders the yellow). In some population, all the unpaired and even Pectoral fins can be bright yellow. Dark botches may appear on the belly or back, but there are usually not many (this distinguishes the Jeweled Splitfin easily from the similar looking Chapalichthys pardalis). Most of the populations have shiny scales on the flankes, in some populations few, but in the ríos Pánuco and Lerma populations, they may cover almost the whole side of the fish.

Males and females of the Jeweled Splitfin are easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Xenotoca variata have a bigger Dorsal fin than females. A third and also very distinct character is the colouration: males have a broad yellow to orange terminal band on the caudal fin, sometimes followed by large black or grey field. Some males have the Anal and/or Dorsal fin also yellow to orange, while females always have clear fins. Usually males are also coloured more intensively than females, but not in all populations. Concerning the colouration of males of different populations see the chapter "Colouration".

The description of Xenotoca variata is a good example for scientists being also just people making mistakes. Tarleton Bean described this species (as Characodon variatus) after only four females he got from Alfredo Dugès from a collection he probably made in Guanajuato (Cat. No. USNM-37809). His description of the colouration (lower half of body with numerous dark spots...) and the drawing (Fig.1) he added to this paper prove this. In the same paper he described Characodon ferrugineus and presented drawings of the types, a male (Fig.3) and a female (Fig.4). He deposited these types under Cat. No. USNM-37810. So far, so clear. Five years later, he declared, that after he got more fish from Dugès, he was "led to believe these two species are identical". Legitimate, by all means, but then he explained that among the drawings he presented five years before, Fig.4 showed the male of variatus with the females just mentioned. Then he described the colouration of the females: "In a large series [...] containing many females, this sex is found to have a narrow dark band along the side, usually well developed, and a very distinct broad dark band occupying the middle of the caudal fin, the base and the tip being pale." This is definitely how a male is coloured, and Fig.4 showed the female of ferrugineus, not a male of variatus, while he pictured a female of variatus under Fig.1. A male ferrugineus is pictured under Fig.3 (see the plate below), but no male of variatus as he didn't have any for the description. Meek again (1904) pictured the female ferrugineus, now correctly named variatus with the collection number given by Bean, while he pictured the male ferrugineus as variatus with the wrong collection number (Cat. No. USNM-37808) that Jordan & Evermann (1896) erronously assigned to the fish. However, the text under the drawings of Meek is conveying, that this is the male type of variatus, designated by Bean, but it wasn't (drawings shown in the chapter "Holotype"). An online check of the GWG in March 2019 resulted in the collection in the Smithsonian holding four specimens under USNM-37809 and two under USNM-37810.

The left picture shows the plate with the original designations by T. Bean (1887), the right one a scheme demonstrating the relationship within the genus Xenotoca (Domínguez-Domínguez, slightly modified):

Xenotoca is a genus in change. While it is meanwhile clear, that the Black and Redtail Splitfins (denoted by the GWG as "Xenotoca" under double quotes) belong to a separate and to be described genus (though "Xenotoca" eiseni was erronously synonymized with variata until 1972), Xenotoca variata as the type species will remain in this genus. However, the populations of the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia drainage differ from Xenotoca variata in many details and will be described in honour of the late Ivan Dibble as a distinct species. The remaining populations are forming four phylogenetically distinguishable lineages with their centers in the ríos Aguanaval and Angulo drainages, the Middle Río Lerma-Verde-Pánuco area, and the Lower Río Lerma-Laguna Chapala area.

Looking on the biotopes of Xenotoca variata, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with rocks, roots and small areas with dense submerse vegetation. Intraspecific aggession is sometimes observed, mostly between males of same size. Fry is sometimes eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 2 to 2.5cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 150 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. A bit with roots and/or rocks structured tanks with few patches of dense submerse vegetation in the corners and bigger free areas to swim seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate, especially as the oxygene level should be quite high (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, adults of this species feed mainly from Crustaceans, worms and insect larvae, partly also from algae and aufwuchs, so much light to help algae grow and feeding with vegetables and additionally fiber-rich middle sized food from animalistic sources will be best for this fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally freeze dried food like Brine Shrimps is eaten greedy. The species is anything else but shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially spring and river inhabiting species. Therefore an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 25°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species does very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15-17°C (depending on population) and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15-17°C (depending on population) by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Xenva1-SMA-JMar

Population: Jesús María (partly erronously distributed as Laguna Magdalena)

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Santa María Alto

Locality: Jesús María dam, about 19km S of San Luis Potosí

2. Xenva1-LPE-Xoc

Population: Xoconoxtle

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Laja

Subbasin: Río Laja-Peñuelitas

Locality: Río San Juán, at bridge E of Xoconoxtle El Grande

3. Xenva1-GUA-PMont

Population: Presa Montelongo (aka Río Guanajuato)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Salamanca

Subbasin: Río Guanajuato

Locality: Arroyo Montelongo, at the Presa Montelongo, 1km E of La Sauceda

4. Xenva1-TPP-AMan

Population: Arroyo La Manzanilla

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Salamanca

Subbasin: Río Trubio-Presa Palote

Locality: Arroyo La Manzanilla, N of León del los Aldama

5. Xenva1-RLL-LMor

Population: Lagos de Moreno

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Verde Grande

Subbasin: Río de Los Lagos

Locality: Arroyo Tútano, at the Presa next to the asphalt company

6. Xenva2-SAH-LNeg

Population: Los Negritos (aka La Alberca)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Sahuayo

Locality: Los Negritos pond, 9.5km W of Sahuayo

7. Xenva3-ANG-LZac

Population: Laguna Zacapú (aka Lago de Zacapu, Zacapu)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Angulo

Locality: Laguna de Zacapú

8. Xenva4-SAA-Ato

Population: Atotonilco

Hydrographic region: Nazas-Aguanaval

Basin: Río Aguanaval

Subbasin: Río Saín Alto

Locality: channels at Atotonilco, about 3.5km SW of Saín Alto

9. Xenva4-RDS-Val

Population: Valenciana (aka la Valenciana)

Hydrographic region: Nazas-Aguanaval

Basin: Río Aguanaval

Subbasin: Río de Santiago

Locality: spring and outflow in Valenciana, about 25km SE of Juán Aldama