- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

"Xenotoca" cf. melanosoma

English Name:

Northern Black Splitfin

Mexican Name:

Mexclapique (erronously: Mexcalpique) negro del norte

Original Description:

undescribed species

Holotype:

undescribed species

Terra typica:

undescribed species

Etymology:

undescribed species

Additionally, this species belongs to an undescribed genus, but until the changement has happened, it stays integrated in Xenotoca. The genus Xenotoca was erected for Characodon variatus by Hubbs and Turner in Turner, 1937, because "this species differs from Characodon (lateralis) in numerous internal as well as external features. Characters distinguishing Xenotoca from Characodon involve the ovarian anatomy, the form and structure of the trophotaeniae, and some superficial features". The generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek with the word ξένος (xénos) meaning strange and and τόκος (tókos) offspring. Xenotoca can therefore be translated with "a strange type of offspring".

Synonyms:

undescribed species

Distribution and ESU's:

The Northern Black Splitfin is a freshwater fish species endemic to the Mexican federal state of Jalisco. It occurs in the endorheic lagunas de Zapotlán, de Sayula, Atotonilco, Zacoalco and San Marcos drainages, the also endorheic Laguna de Magdalena drainage and sections of the Upper Río Ameca like the Río Chiquito drainage W of Etzatlán, the Río Salado W of Guadalajara and the arroyos Hondo, El Saltre and San Martín. From its affiliation to different drainages, six subpopulations can be inferred: The Laguna de Zapotlán subpopulation, the Laguna de Sayula subpopulation, the Laguna Atotonilco subpopulation, the Upper Río Ameca subpopulation, the San Marcos subpopulation and the Laguna de Magdalena subpopulation. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In "Xenotoca" cf. melanosoma we are able to distinguish several ESU's. Xenme1 is used for the Río Ameca populations and Xenme4 for those of the endorheic Laguna de Magdalena basin, but needs evaluating as probably the stocks from San Marcos, Granja Sahuaripa and near the border to Nayarit are closer related to the Laguna Magdalena stocks as to the other ones from the Río Ameca. Xenme2 seems to be clear and encompasses all populations from the endorheic basins from Atotonilco down to Zapotlán, though the fish from the Laguna de Zapotlán are phylogenetically distant to the ones of the two other drainages. Xenme3 is in use for the "true" melanosoma from the ríos Ayuquila, Tamazula and Tuxpán.

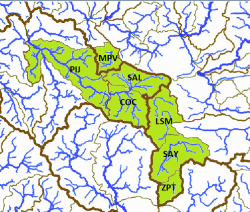

The left map shows the Río Santiago-Aguamilpa (SA) and Lago de Chapala (CH) basins from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago and the Presa La Vega-Cocula (VC) and Río Ameca-Atenguillo (AA) basins from the Hydrographic Region Ameca on a Mexico map. The right map shows the different subbasins where the Northern Black Splifin occurs. It inhabits more or less a continuum of habitats from the endorheic Laguna Magdalena-Laguna Palo Verde subbasin (MPV) with members of the ESU Xenme4, and adjacent creeks and ponds in the ríos Ameca-Pijinto (PIJ), Salado (SAL) and Cocula (COC) subbasins, populated with representatives of the ESU Xenme1, to the endorheic subbasins of the lagunas de San Marcos (LSM), de Sayula (SAY) and de Zapotlán (ZPT). Here occur fishes of the ESU Xenme2:

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): not assessed (undescribed species)

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Vulnerable/declining (including "Xenotoca" melanosoma): „This species is found in the Santiago, Ameca, Armería, and Coahuayana river basins and the endorheic Magdalena, Atotonilco, San Marcos, Zacoalco, Sayula, and Zapotlán lake basins in Jalisco (Miller et al., 2005). We recognize four ESUs based on genetics and zoogeography (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2010; Mar-Silva, 2018). Xenme1 is by far the most numerous and widely distributed and is classified as vulnerable. It is found in the Ameca, Magdalena, Atotonilco, San Marcos, Zacoalco, and Sayula basins at a total of ca. 15 locations. It has declined since 2000 owing to water pollution, habitat degradation, and non-native species. It has disappeared from the San Marcos and Zacoalco basin and persists at only 1–3 locations in the Magdalena, Atotonilco, and Sayula basins. The best remaining populations are in the Ameca basin. Xenme2 is critically endangered and is known from Lake Zapotlán where it is rare and in decline from habitat modifications and non-native species. Xenme3 is endangered and currently known from two locations on the upper Tamazula River where it is threatened by water diversions and introduced species. Xenme4 is also endangered and is limited to a short reach of the Ayuquila River downstream of the city of El Grullo in the Armería River basin, where chronic water quality degradation limits the population.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

This species lives in ponds, streams and lakes with clear to muddy water (sometimes badly polluted) over substrates of mud, sand, gravel, rocks, boulders and bedrock. There is eiher no vegetation or green algae, Cyperus, Eleocharis, Potamogeton, water hyacinths, Lemna, Nasturtium, Scirpus and Typha. The currents are none to moderate and like most of the Goodeids, it prefers depths of less than 1m.

On a GWG survey in March 2016, the group found this species in a clear spring on a private property in La Estancia de Ayones between waterplants of the genera Potamogeton, Eleocharis and Myriophyllum. The diameter of the spring was about ten meters. Other species were Goodea atripinnis, Zoogoneticus purhepechus, Poeciliopsis infans and Tilapia. In an artificial fish pond opposite Palo Verde lagoon, the species lived in plantless muddy water together with Zoogoneticus purhepechus, Goodea atripinnis, Allotoca maculata, Poeciliopsis infans and again Tilapia and Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus. A similar habitat was the spring pool at the Hacienda San Sebastian, the type location of "Xenotoca" doadrioi. At Almoloya spring, they found a single specimen in brownish and little murky water. The species was associated with Ameca splendens, "Xenotoca" doadrioi, Zoogoneticus purhepechus and Goodea atripinnis as well as Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus and Tilapia. Another habitat was the Presa Quemada north of the Magdalena lake. Here the species occured over gravel in turbid water, moved by strong winds. It was associated with Goodea atripinnis, Poeciliopsis infans and Tilapia. On a survey to habitats southeastern of this area in November 2018, the members of this GWG survey were able to find the Northern Black Splitfin in very low numbers in the Laguna de Zapotlán and in creeks and dams of the Upper Río Ameca drainage. A quite strange habitat was the outflow of a thermal spring in San Marcos, endorheic Laguna Atotonilco drainage, where the species occured more or less directly in the mud of this outflow. It seems to be not very abundant in the habitats as it is rarely observed.

Biology:

Young have been captured in late spring, indicating a reproduction from at least March to May. On a survey of the GWG in March 2016 to the Laguna Magdalena basin, several pregnant females but no fry was found. Young specimens of 2cm standard length were seen in the endorheic Laguna Atotonilco and de Zapotlán basins, indicating a reproduction in this area by the end of the rainy season between August and October.

Diet:

The dentition is similar to "Xenotoca" eiseni suggesting an omnivorous feeding behaviour, nevertheless feeding predominantly on aquatic animals and lesser amounts of algae and aufwuchs. As Black and Redtail Splitfin mostly occur as a species pair, it is very likely, that they use different food sources. In this case, the Black Splitfins are the more carnivorous representatives of the genus while the Redtail Splitfins feed mainly from herbivorous food sources.

Size:

The maximum known standard length is 85mm (Miller et al., 2005).

Colouration:

The colouration is very similar to "Xenotoca" melanosoma with females displaying a serious of black blotches on the sides, fading when becoming adult except fot the caudal peduncle, where the blotches stay clear and distinct. Then the females appear dark grey or dark brown. In some populations, these blotches are vertically elongated forming indistinct stripes. Males show vertical stripes on the sides, also fading when getting older, and being replaced by a unicoloured brown, copper or golden, changing into a dark grey or black in some populations when courting. The colour of the body is dark brown or dark grey with the venter being usually lighter, whitish or creme, the fins are clear but change into a dark grey or black in males of some populations when courting.

Sexual Dimorphism:

At first appearance, males and females of the Northern Black Splitfin are not very easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male "Xenotoca" cf. melanosoma have a much bigger Dorsal fin than females. Differences in colouration are poor. Like in its relative "Xenotoca" melanosoma, females show a row of dark blotches in the midline while males rather have fading vertical stripes on the posterior half of the body with the part along the midline being more intense. The area between opercle and Dorsal fin is sometimes spotted in males. Old individuals of some populations become unicoloured copper to dark grey, males almost black when courting.

Remarks:

Already hybridisation studies of Fitzsimons (1972) revealed a close relationship of "Xenotoca" melanosoma with "Xenotoca" eiseni, but not with Xenotoca variata. The Redtail Splitfin, its closest relatives (doadrioi and lyonsi) and the two species of Black Splitfins do not belong to the genus Xenotoca. Shane Anthony Webb (1998) proposed a new generic name in his thesis for these species, that has not been published officially (Xenotichthys). The reason therefore is the US-American jurisdiction, that a thesis doesn't count as an official publication. Therefore R. R. Miller segregated the generic name by quotation marks, a system, we follow in the GWG.

The species cooccurs in some areas with populations of "Xenotoca" doadrioi, forming a species pair between Redtail and Black Splitfins, like it can be found almost everywhere where a representative of these species lives, except for Nayarit and "Xenotoca" eiseni. Phylogenetic tests (Domínguez-Domínguez, 2011; Mar-Silva, 2013) support that the populations from the ríos Armería and Coahuayana drainages are conspecific and form a lineage, that is clearly recognizable and distinct from the populations north of these basins. The type location of "Xenotoca" melanosoma is the Río Tamazula, so the southern populations are what we call the "true" melanosoma, while the northern populations belong to this separate to be described species.

Husbandry:

Looking on the habitats of "Xenotoca" cf. melanosoma, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with rocks, roots and small areas with dense submerse vegetation. Intraspecific aggession is sometimes observed, mostly between males of same size. Fry is eaten in most of the cases, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 2 to 2.5cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 250 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. A bit with roots and/or rocks structured tanks with few patches of dense submerse vegetation in the corners and bigger free areas to swim seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate, especially as the oxygene level should be quite high (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, adults of this species feed mainly from Crustaceans, worms, insect larvae and other middle sized invertebrates, but also from aufwuchs, so feeding with fiber-rich middle sized food from animalistic sources will be best for this fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally freeze dried food like Brine Shrimps is eaten greedy. The species is a bit shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially spring and river inhabiting species. Therefore an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 25°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species does very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C (depending on population) and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C (depending on population) by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Xenme1-PIJ-GSah

Population: Granja Sahuaripa

Hydrographic region: Ameca

Basin: Río Ameca-Atenguillo

Subbasin: Río Ameca-Pijinto

Locality: an affluent of the Canal del Bajío at the (former) Sahuaripa Ranch about 1.7km E of San Marcos

2. Xenme2-LSM-SMAto

Population: San Marcos-Atotonilco (aka Laguna San Marcos)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Laguna Chapala

Subbasin: Laguna de San Marcos

Locality: a spring area in San Marcos, Laguna de San Marcos, about 30km SW of Guadalajara

3. Xenme2-ZPT-Zapo

Population: Laguna de Zapotlán

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Laguna Chapala

Subbasin: Laguna de Zapotlán

Locality: E coast of the Laguna de Zapotlán

4. Xenme4-MPV-PaVer

Population: Palo Verde

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Santiago-Aguamilpa

Subbasin: Laguna Magdalena-Laguna Palo Verde

Locality: an artificial pond 50m S of the Palo Verde lagoon W of Etzatlán

5. Xenme4-MPV-EAyo

Population: Estancia de Ayones (aka Estancia de Allyones)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Santiago-Aguamilpa

Subbasin: Laguna Magdalena-Laguna Palo Verde

Locality: a private spring in La Estancia de Ayones