Skiffia lermae

MEEK, S. E. (1902): A contribution to the Ichthyology of Mexico. Publication. Field Columbian Museum. No 65, Zoological Series 3 (6): pp 63-128

Collection-number: Field Columbian Museum, Cat. No. FMNH-3616.

The Holotype has got 54.1mm standard length (the sex is not mentioned in the description and hasn't been checked in the museum by the GWG so far), collected by S. E. Meek and F. E. Lutz, from May 19th to May 21st, 1901. Entries in the FMNH and the CAS for fish of this collection say erronously May 18th, 1901. Together with the Holotype were taken more than 150 specimens, preserved under several collection numbers in the Field Museum of Natural History (the former Field Columbian Museum) and the California Academy of Sciences.

The female Holotype of Skiffia variegata (FMNH-3612) was collected together with more than 100 specimens on May 24th, 1901, by the same collectors from the Zirahuén lake, preserved under several collection numbers in the Field Museum of Natural History and the United States Museum (the Smithsonian). Concerning one entry for Chalco, go to the chapter Holotype under Allotoca diazi.

The pictures below show a male (left) and female (middle) Paratype of Skiffia lermae and the Holotype (right) of Skiffia variegata:

The types of the Olive Skiffia were collected in the Lago de Pátzcuaro near the town of Pátzcuaro, Mexican federal state of Michoacán.

The species is probably named for the basin of the Río Lerma, though the type locality of this species is the Lago de Pátzcuaro that belongs to a different drainage. Eventually this hydrological situation wasn't clear at the beginning of the last century and Meek thought indeed, that this lake belongs to the Lerma basin.

The genus was erected by S. E. Meek in 1902 to honour Frederick James Volney Skiff, the 1st director of the Field Columbian Museum. Taking the latinized female version of his surname, Skiffia can be translated with "Skiffs one".

Skiffia variegata Meek, 1902

Goodea lermae Regan, 1907

The Olive Skiffia is endemic to the Mexican federal states of Michoacán, Guanajuato and Querétaro. It was historically reported from the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia basin including the Lago Cuitzeo and the Presa Cointzio, from the Laguna Yuriría and several spring areas (La Mintzita, La Maiza, San Cristobal) draining into the Río Grande de Morelia respectively Lago Cuitzeo. It is furthermore known from the endorheic Laguna Zirahuén and Lago de Pátzcuaro basins, from the Río Angulo drainage including the Lago Zacapú and from habitats along the Middle Río Lerma, at least from a spring near San Francisco del Rincón, Río Turbio drainage and from the Río Laja system. There is one report from this species from the Presa El Centenario near Tequisquiapán, Río San Juán drainage (a Río Pánuco affluent), so it even reached the headwaters of this river. Distribution and abundance of Skiffia lermae have declined steadily over the last 50 years with continued losses through the 2000’s. The species disappeared from the Laja River, Lake Yuriría, Lake Cuitzeo, and the entire Lake Zirahuén basin, and has become uncommon and limited to a few small springs in the Lake Pátzcuaro and Grande de Morelia River basins (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1998, 1999; De la Vega-Salazar, 2003; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005, 2008; Mercado-Silva et al., 2006). At present, only about six sites remain, the largest of which are in Lake Zacapú in the Lerma River basin, the Molino de Chapultepec Springs in the Lake Pátzcuaro basin, and the La Mintzita Springs in the Grande de Morelia River basin (Lyons, 2011). According to different drainages, seven subpopulatios are distinguished: The Lago de Pátzcuaro subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Río Grande de Morelia subpopulation, the Río Angulo subpopulation, the Middle Río Lerma subpopulation, the Río San Juán subpopulation, the Laguna Yuriría subpopulation and the Laguna de Zirahuén subpopulation. The last four subpopulations are regarded extinct. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of the first 3 letters of the genus, followed by the first 2 letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Skiffia lermae, we have the possibility to distinguish four ESU's: The first unit Skile1 encompasses populations from the middle Río Lerma, including fish from the Lago de Zacapú, Río Turbio and Río Angulo. The second ESU - Skile2 - is used for fish from the endorheic Río Grande de Morelia basin and the Yuriría lake, including the Lago de Cuitzeo and several springs like La Mintzita, La Maiza and San Cristobal. ESU number three, Skile3, is in use for the populations from the lakes Pátzcuaro, the type location of the species, and Zirahuén, the type location of the former Skiffia variegata, now a synonym of Skiffia lermae. The last ESU, Skile4 is reserved for fish from the Laja river and adjacent habitats in the Pánuco river system.

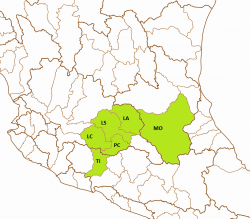

The left map shows the Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria (PC), the Río Lerma-Chapala (LC), the Río Lerma-Salamanca (LS) and Río Laja (LA) basins from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, the Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo (TI) basin from the Hydrographic Region Balsas and the Río Moctezuma (MO) basin from the Hydrographic Region Pánuco on a Mexico map. The Olive Skiffia was known from the Lago de Zirahuén (ZIR) subbasin, Río Tepalcatepec-Infiernillo basin and the Drenaje Caracol (DCA) subbasin, Río Moctezuma basin. It seems to be gone from both of these basins. The same fate might have reached the populations from subbasins from the ríos Laja and Lerma-Salamanca basins that were historically populated with this species. There are from the Río Lerma-Salamanca basin the Río Salamanca-Río Angulo (SAN) subbasin, the Río Solís-Salamanca (SOS) subbasin, the Río Guanajuato (GUA) subbasin, the Río Turbio-Corralejo (TCO) subbasin, the Río Turbio-Manuel Doblado (TMD), and the Río Trubio-Presa Palote (TPP) subbasin. From the Río Laja, the species was known from the ríos Laja-Celaya (LAC) and Apaseo (RAP), and from the Presa Ignacio Allende (PIA) subbasins. The species still occurs in the Río Angulo (ANG) subbasin from the Río Lerma-Chapala basin, and the lagos de Cuitzeo (CUI) and de Pátzcuaro (PAT) subbasins from the Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Lago de Yuriria basin. From the Lago de Yuriría (YUR) subbasin from the same basin, it is probably gone. All subbasins mentioned are shown on the right map:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Endangered/declining: „The historical range of this species encompassed many sites in central Mexico including Lake Zacapu, Lake Yuriria, and the Laja River in the middle Lerma River basin, and the endorheic Lake Pátzcuaro, Lake Zirahuén, and Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basins. Distribution and abundance of S. lermae have declined steadily during the last 50 years, due to water pollution, habitat degradation, and non-native species, with continued losses through the 2000s. The species has disappeared from nearly all of the Laja River drainage, Lake Yuriria, Lake Cuitzeo, and the entire Lake Zirahuén basin, and has become uncommon and limited to Lake Zacapu and a few small springs in the Lake Pátzcuaro and Grande de Morelia River basins (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1998, 1999; De la Vega-Salazar, 2003; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005, 2008; Mercado-Silva et al., 2006). Four ESUs are recognized, all in trouble. Skile1 occupies Lake Zacapu in the middle Lerma River basin where it is endangered. Skile2 has been reported from Lake Yuriria and the endorheic Lake Cuitzeo/Grande de Morelia River basin and is endangered. Populations from Lake Yuriria and Lake Cuitzeo are gone, but this ESU persists in the La Mintzita Springs, tributary to the Grande de Morelia River. Skile3 is known from the endorheic Lake Zirahuén and Lake Pátzcuaro basins and is also endangered. This ESU has been eliminated from Lake Zirahuén and Lake Pátzcuaro but persists in the Molino de Chapultepec Springs in the Lake Pátzcuaro basin. Skile4 is known from the Laja River drainage and is critically endangered. Historically this ESU was common throughout the drainage but now it is restricted to the Charco del Ingenio Reserve on the De Las Colonias Reservoir in the city of San Miquel de Allende, Guanajuato.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): A - Amenazada (threatened)

The habitats are quiet waters of lakes, spring-fed ponds, canals and small creeks with clear to turbid water over mud, sand, gravel and decayed organic matter. The vegetation comprises green algae, Eichhornia, Lemna, Scirpus, Salvinia, Nasturtium and Potamogeton. The species prefers usually depths of less than 1m. The currents are none to slow.

The GWG found this species on several surveys to the Zacapú lake (2014, 2016 and 2017), the spring near the old mill in Chapultepec (Pátzcuaro lake drainage, 2014 and 2017) and the La Mintzita spring near Morelia (2014 and 2015). In the Chapultepec habitat, the Olive Skiffia was partly found in dense submerse vegetation of Elodea or Egeria, and partly net to the bank in faster flowing channels, however trying to avoid the fastest flowing parts. In January 2015, it was seen in the dammed spring fed pond courting and impressing females, the males beautifully coloured with yellow caudal peduncles with a dark black head, the females with a yellow belly. Fish in the Zacapú lake were found close to the bank, next to roots of willow trees, but not directly in. In La Mintzita it seemed to be quite common, even on underwater films it was one of the most numerous species (only outnumbered by Xenotoca cf. variata).

Underwater-Videos:

Following Miller, the reproductive period lasts from at least February to May, indicated by newborn young or pregnant females. He also documented this species swimming just beneath the surface in full sunlight, the young often in groups of three to fifteen.

Meek described the intestines as elongated at 2 to 3.5 times as long as the body and coiled on the right side, the teeth as loose and bicuspid in the outer row, small and villifom in the inner row. As an omnivorous species with mainly herbivorous feeding habits, this species is mainly grazing aufwuchs, for example from submerged Scirpus stems, and algae. It is also attracted by insects on the surface. On surveys of the GWG to Chapultepec, several specimens could be observed nibbling from rocks and submerse plants respectively stems of reed.

The groundcolour of both sexes is olive to champagne-coloured, darker on the dorsal side and brighter on the belly, all fins mostly clear. Some individuals, mostly females, rarer males, display smaller or bigger black spots and blotches, giving them a marbled appearance, but most of the individuals are almost unichrome. Dolores Kingston described Skiffia lermae males to be very colourful, displaying bright orange caudal peduncles and caudal fins and blue to black heads. This colouration describes the breeding colour of males, as in contrast to its congeners, male Skiffia lermae are coloured intensively exclusively during courtship. Then males indeed show dark black heads and a yellow to orange body, or at least caudal peduncle, while females express at least the belly in striking to dark yellow. Interestingly these colours disappear quickly in photo tanks and the fish are back to normal colouration within fifteen minutes.

At first appearance, males and females of the Olive Skiffia might not always be easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Skiffia lermae have a much bigger and notched Dorsal fin than females, giving it a serrated appearance on its anterior part. When males court, it is much easier with males getting a black head and the posterior half of the body becoming striking yellow, while females show a typical yellow belly, but this colouration is just temporarily and disappears within minutes when fish are disturbed or out of mood.

Meek described in 1902 not only Skiffia lermae from the Pátzcuaro lake, but also Skiffia variegata from the Lago de Zirahuén. Following Meek, variegata differs from lermae by being more slender, in the absence of a caudal bar and by differences in the colouration. He also remarked this species to be the smallest of the genus. Both species were already synonymized by Regan (in the book "Pisces, 1906-08), variegata reestablished by Hubbs & Turner (1939), but finally synonymized by Miller & Fitzsimons in 1971. The population of the Zirahuén lake is meanwhile extinct, so further studies not possible. However, it is not doubted today that Skiffia variegata is conspecific with lermae. Besides that, the name Skiffia lermae appears several times in samplings of fish from the Lower Río Lerma basin, including the Río Duero, the Lago de Chapala and even from the Laguna de Sayula. All of these identifications have to be regarded as misidentifications with Skiffia multipunctata or - in case of the Laguna de Sayula collection - Skiffia francesae. Skiffia lermae differs from multipunctata mainly by its thin and elongated caudal peduncle, the smaller dorsal fin, the more slender bodyshape, the smaller size and the colouration, so lermae rarely shows big black blotches on the sides (and if so, then in a different way), and it is characterized by the typical colouration of the males during courtship.

Looking on the biotopes of Skiffia lermae, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with none to moderate current, structured with gravel, rocks, roots, branches, fallen leaves and submerse or/and river bank vegetation. Fry is usually not eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide, so it is easy to get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 60 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With few rocks or roots and dense vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate, specially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from algae and aufwuchs, but also from small invertebrates, so feeding with similar food like algae grown on feeding stones, blanched or boiled vegetables, water fleas and other small food from animalistic sources will be best for this predominantly herbivorous fish. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is not really shy, but likes to use hiding spots to observe the surrounding.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (24°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Skile1-ANG-LZac

Population: Laguna Zacapú (aka Lago de Zacapu, Zacapu)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Angulo

Locality: Laguna de Zacapú

2. Skile2-CUI-LMin

Population: La Mintzita (aka La Mintzita spring, Manantial La Mintzita)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Lago de Pátzcuaro-Cuitzeo y Laguna de Yuriria

Subbasin: Lago de Cuitzeo

Locality: Manantial La Mintzita, about 5km SW of Morelia